Your game has a face. No, I’m not talking about your uber-cool protagonist’s lady killer, I’m talking about what players literally see the most in your game; Its’ environment. In this article, you will find out about the most common challenges developers face during the game environment design process.

Every game art studio has its own approach to the game design & development process. However, the challenges and obstacles they have to overcome are pretty much the same.

One of the most demanding and rewarding aspects is defining a visual identity (style) for your game-to-be; a complicated undertaking that is done through collaboration between the game’s creative and art director.

Considering that a game reflects its visual identity mostly in a game’s environment, the importance of designing a functional and unique environment is paramount. Note that in this article, the term “game’s art” often points to “game’s environment art”.

This article talks about the design challenges of a game’s environment, but that topic is heavily interlinked with game level design. The environment and level design teams always work hand in hand, so some of the following challenges are about level design just as much as they’re about environment design.

Game environment design is just one part of the art that goes into creating a game. If you’re new to these topics I highly suggest you read our post about game art first.

There we have briefly talked about every aspect of creating art for games, including their environments.

1. Creating an Efficient Link Between the Team

As mentioned before, every game studio has its own way of approaching game development. That includes their own unique organizational charts. Regardless of titles and positions, everyone working on a game need to share a single vision.

Creating a strong link between level designers, environment designers, and creative/art directors results in a game with an environment that is in harmony with the rest of the game, it also means less misunderstanding and time wasted on reworking stuff.

One issue that many game studios still fail to address is to create an effective connection between the art director and narrative designer since the concept stage. If the gameplay is what players do in a game, then the story is why they do it. The story and the art of the game have to complement each other.

To give a blunt example: In a children’s storybook about a young hero defeating a dragon, you won’t use sharp, gory pictures of dragon’s victims with their guts spilling out. But if you only tell the book illustrator that the game is about dragons, he might give you game of thrones dragons, while you were looking for something like Spyro.

The art director knows best “how” to visualize and create different objects in a room. A narrative designer knows “what” objects should be in the room to create that feeling of horror, excitement, or motivation in the players. That is mainly why these two positions have to collaborate at the very beginning of the project.

In short, to get the best result, everyone needs to be on the same page. Read more about organizing a game project here:

Game Development for Noobs: Organize Your Project Like a Pro

That post will be especially exciting for those game lovers who are thinking about creating their own games.

2. Following the Visual Identity

Each game should have its own clear visual identity. That means every part of it follows a specific design style and structure. To define visual identity we might use phrases like retro 8bit graphics, pixelated with lively colors, hyper-realistic noir style, etc.

The visual identity should be in harmony with the core concept of the game, and it must agree with our budget and limitations. Some styles require more time and effort than others, but that doesn’t mean they’re “better” though.

Aim big without conscious decision making and you’re likely to fall short of reaching your goals. One prime example of this is Mass Effect: Andromeda. Devs packed Andromeda with new features to bring life to the old Mass Effect series.

Especially the big change in shifting from linear levels to an open-world environment. Marketing created massive hype and excitement for the players, but after launch, it became clear that the dev team at BioWare Montreal was way over their heads.

Problems like confusing level design, ridiculous facial expressions, and clunky animations were partly the result of failing to set the proper scope & scale when BioWare conceptualized the game at the beginning; causing a big game from a popular IP to (relatively) fail.

Creating (or outsourcing) the games’ art is perhaps the most expensive part of game development. So it goes without saying that it is utterly vital to define a proper art style at the conceptualizing stage.

The style not only complements the other parts of your game but also manages to stay within the scale of the project and its’ budget. The real question here is not “How far can we go with the game’s visuals?” but “How far can we go without sacrificing the quality of the work?”

Case Study: Darkest Dungeon

In January 2016 a very small team created their first game that didn’t belong to any IP, famous or not. The game’s visual style was simplistic with an environmental design that used the assets again and again (smartly so, we’ll cover this one later on in this article).

Almost the entire gameplay consisted of rolling dice and the bits of the story it provided were highly stereotypical. Taking those facts in alone, it should then come as a surprise that Darkest Dungeon sold over 2 million copies. It was both a huge commercial and a critical success.

Darkest Dungeon’s director Chris Bourassa -Who also did a large part of the game’s art- didn’t have access to the endless resources of a company like BioWare.

He couldn’t go for a photorealistic 3D game world with scenery that resembled a postal card. Instead, he did a superb job of creating an environment in perfect harmony with the rest of the game.

It didn’t matter how short the story was, players could keep “reading” the story in its environment. Repeated use of simple environments and assets didn’t bother most players. Why? because the story (and gameplay) was also simple, small, and in harmony with one another. Every bit of Darkest Dungeon screamed the word & concept “Dark”.

3. Choosing Between the Linear and Non-linear Designs

Making decisions about this one should be clear and straightforward to the project’s budget and time constraints. Before we continue, we will provide a concise definition of the terms used in this section.

Linear games use heavily scripted level designs that predict and design the route and the events players will experience during their play. Rocks will fall exactly if (and every time) players pass through block X in the game.

To reach area B, you must first cross area A. This approach provides for a more cinematic and controlled experience for the players. Prime examples of such games are the Uncharted and Half-Life series.

Non-linear games emphasize emergence gameplay and usually function as a sandbox. Players experiment and create their own unique style of gameplay in such games. In these titles, the game environment plays a vital part in telling the game’s story. Minecraft and Far Cry series are good examples of the emergence approach.

Key Differences of Linear and Non-linear designs:

These two approaches have major differences when it comes to game environment design.

- Games with emergent gameplay and especially those with open-worlds often require a massive budget compared to games with a scripted approach.

- Game environment design has different governing principles between linear and non-linear games. For games with emergent gameplay, it is doubly important that the environment reinforces an overarching theme and setting.

It is worth noting that although there has been a steady increase in the number of games that choose to go for open-worlds, not all of them provide for emergent gameplay. Note that having an open world is by no means vital to a game’s success.

4. Maintaining Visual Clarity: Sometimes More is Less

The game environment is what you see the most while playing. They provide a scenic background for the place where players are performing actions and interacting with other characters. NPCs, enemies, and PCs all operate within the game environment.

Ironically enough, the environments are rarely the place where the players’ focus should be directed.

The game environments should not obscure the action happening on screen or cause confusion for the players in any way.

On the contrary, they should reinforce and support the main action through various means (such as creating contrast). This is particularly true with special effects and particles.

If players can’t properly detect the incoming arrow or magic missile and react to it in time because of the environment, we as environment designers have impeded their ability to enjoy the gameplay.

This could be due to too much clutter in the environment. Or, improper use of textures and colors that obscure the characters or particles.

Each game genre has its own set of specific visual clarity challenges to overcome but the desired outcome is the same in all of them; providing the players with visual clues and information as smoothly as possible, in such a way that the players can take in all the information they need without feeling confused or overwhelmed.

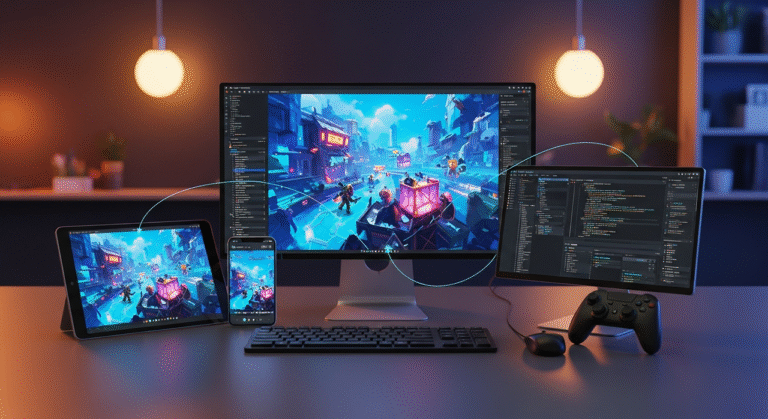

You could take a look at some of Pixune’s environment designs that we did for mobile games. Notice how each visual element work together to provide the player with a clear image of what is going on in the game.

5. Making the World Feel Authentic

During the early stages of Assassin’s Creed 2 development, the art team was sent to present-day Florence and Venice for a couple of months to get a feel of what these cities looked like during the Renaissance. They spent their days there just taking in the view.

Those marvelous cities offered them and sketching every now and then of something coming across as especially interesting to them. Needless to say, it cost Ubisoft a great deal of capital, but the outcome speaks for itself. Assassin’s Creed 2 is a magnificent game due in no small parts to its’ breathtaking environment design.

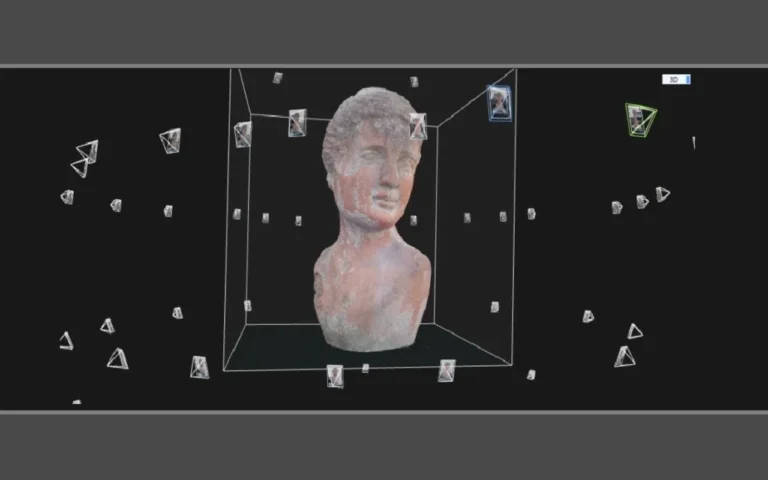

The surest way to imagine new things that impresses any viewer is to use reality as a foundation to build our own imaginative creations upon.

The results of such a creative process will feel real and authentic to players even if they had no beforehand knowledge of how Venice or Florence looked like during the Renaissance or even now.

Case Study: The Witcher 3

Another great example is that every major city in the dark fantasy world of “The Witcher 3” is based on a real city in Poland. One of the main reasons for the success of reality-based imagination is because there are such details found in the real world that we might have never imagined by ourselves.

It is the smallest details and touches that separate a game world that eases the immersion process for the players from one that actively hinders it.

Note that paying attention to detail is not the same as using too much detail when designing the game’s environment which itself could potentially harm the visual clarity of the game.

Worldbuilding is heavily intertwined with game environmental design, and it is one of the key undertakings that should be done with the collaboration of the art director and the narrative designer.

6. Immersion: Connecting the Narrative With the Environment

Immersing a player in your game through its environment is perhaps the most important job of an environment designer. That’s why we will talk about this particular challenge more than others.

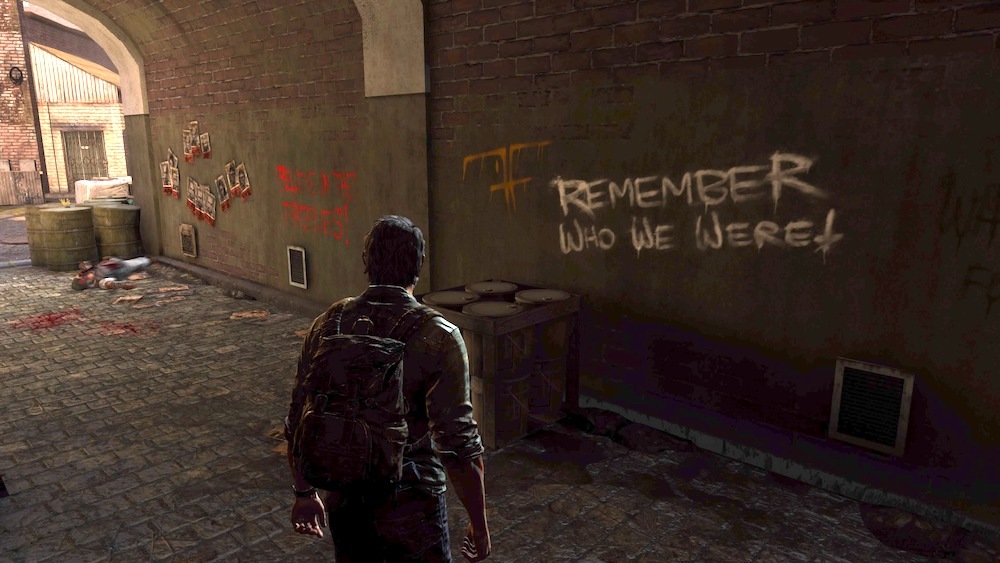

Environmental storytelling is a way of delivering the game’s story (or parts of it) through the gameplay system and the game world itself in a nonlinear fashion without explicitly telling players what’s happening through cut scenes or dialogues. It is the visual cues, the scenery, the props, and the placement of assets.

Environmental Storytelling is an experience that players can only have within a carefully designed interactive environment of a video game.

One of the main focus of a game is to keep a player engaged and “immersed” in your game. If you can feed them information without directly shoving a lot of info in their brain then that’s a big win both for the developer and for the player enjoying the game.

The idea behind environmental storytelling is that by simply adjusting the environments and changing the way your levels are laid out you can already provide a lot of narrative context and information about the world and it’s happening to the player while at the same time making them feel good for essentially figuring it out themselves.

Why do We Employ Environment Storytelling?

Telling non-linear stories through the objects in the environment is a great and relaxed way of conveying the game’s lore and story without overwhelming the players with too much text or expensive cut scenes.

Consider that players spend time with a game to “play”, and not to “read” or to just simply “watch”. Environmental storytelling (especially so when it’s interactive) comes off as a natural medium for video games to create depth upon their more conventional narrative elements such as cut scenes, dialogues, or companions.

Besides carrying the burden of complementing the game’s narrative, when done properly, environmental storytelling piques players’ curiosity and creates the urge to explore the game levels.

Mostly because they don’t want to miss any bits of the story is hidden in-game levels by developers. This ensures that all the efforts that level designers put into creating intricate and expansive levels won’t go to waste. Also, the players will have a better overall experience navigating through those levels.

It is important to note that when discussing environmental storytelling, we are not talking specifically about the surface of the environment or still-objects, but rather everything that adds value and enriches our environment to turn it from simply an interactive game level to a make-believe world that we might have dreams (or nightmares!) about.

Let’s go through some find examples of video games that made great use of environmental storytelling and how they did it.

Case Study: Metro game (Audio Logs)

franchises are well-known for creating awesome post-apocalyptic environments that are packed with stories. One thing in particular that the studio got right was the mixture of carefully placed audio logs throughout the game.

Imagine seeing a spooky skeleton huddled up at the end of a tunnel shaft. The wall beside it is repeatedly scratched to mark the passage of days.

This tells the players the story of a man who waited out his last days in the darkness of the sewers for help that never came.

Now combine that with an old tape recorder found beside the skeleton’s bedroll that tells the story of how he spent those last days with the shaky voice of a terrified survivor. Then you have a player who develops real emotions toward an imagined world that you made up.

Case Study: Wolfenstein (Incidental Dialogues)

The modern reboot of the Wolfenstein franchise does a fantastic job of implementing environmental storytelling through incidental dialogues between Nazi soldiers.

Even for a full-fledged action game that uses adrenaline rush as its main selling point, good stories are necessary; As mentioned before, stories give the real reason to players to continue playing the game. Because the initial hype of gameplay excitement soon worn out.

Id Software employs incidental dialogues for more than just the purpose of adding layers to the main plot. In an exaggerated violent game with a fast pace, careful placement of “time-outs” becomes necessary for players to have a breather between intense action sequences to set a balanced rhythm for the game.

Incidental dialogues in this game sometimes provide for a comic relief effect. Imagine when you hear ironic or even down-right stupid conversations two Nazi soldiers have about whose mustache is more “Ariyan”.

It also acts as a subtle moral compass, as a reminder that the enemies you are mowing down left and right are actually human beings that were simply born at the wrong place and the wrong time, it helps players to mindlessly fantasize about killing, something that may have real consequences in their real lives in the real world.

Case Study: Left 4 Dead (Deliberate Object Placement)

This is by far the most commonly used method of environmental storytelling and is something that Left4Dead is exceptionally good at.

Many parts of the story are for the players to interpret, they are open-ended. This is perfect for a game like Left 4 Dead that hardly ever gives a moment for players to rest and reflect.

Seeing a bottle of painkiller pills on a nightstand beside the bed where 2 corpses have lied down in a tight embrace implies a silent love story.

A couple who rather facing the horror of the zombie apocalypse (the game world), decided to commit peaceful suicide. Players can take all that information in with a moment-long glance and get back to mowing down hordes of mindless zombies.

7. Engaging Players’ Imagination

While this factor is true for all the games out there; It is especially important for indie developers as they can easily lower the production costs.

This also adds a layer of subconscious immersion to their game by borrowing the brainpower of the players to do half the job for them. This may sound like a scam by game developers but it is actually a smart way of creating a game world that is also rewarding and engaging for the players.

The important thing here is not to get stuck trying to make everything absolutely clear for the player. At some point, the player themselves needs to make the leap and connect the dots to create a unique and personal narrative for themselves.

The idea is that all the information should not be right there for the player to just consume info and move on. instead, it might sometimes take a bit of a closer look or a bit of thinking about what’s around the player to give an understanding of what that place is and what the overall context is.

in this sense, even if some players end up identifying a certain situation slightly differently than you as the developer had in mind.

The goal here is to make players see what’s not there!

Having somewhat varying interpretations of the same game isn’t necessarily bad unless it’s completely on the opposite spectrum of what you intended for the game to be.

This is compelling because the game invites more investment and immersion from the player whilst creating emergent gameplay in the form of connecting clues and hints. It also gives the player the feeling of solving the situation on their own rather than having their handheld through the entire game.

AAA games made big-name companies often try to get every bit of detail they can into their games. Creating picturesque, photorealistic images that are impressive to behold but leave nothing for the imagination.

Case in point, smart use of elements like fog and dimly lit rooms could, in fact, be more exciting for the players rather than showing what is exactly on the other side of that fog, or what objects are placed in that room.

8. Building a Game World that Feels Alive

Your game has a face, but it also has a character. And like in reality, it is far easier to see a face than to discern the character hidden beneath it. Accordingly, in the game environment design, the most difficult part is perhaps implying and pointing toward the character of the game’s world through the surface of the environment.

Creating breathtaking sceneries requires a good command in the field of aesthetics. However, creating breathtaking scenery that feels like it really exists requires more than that. This is also one of the challenges where the efficient collaboration of narrative designers and art directors plays a vital role.

The goal here is to make players feel that events in that world would continue even if he/she wasn’t there. The game world wasn’t created only so that it could tell the story of the game’s protagonist.

On the contrary, players should feel like they are intruders, someone to throw off the status-quo that was present in that world before they pressed “New Game”. Players should feel what they are experiencing is just a part of what’s happening for that world and its inhabitants.

Now that the underlying design philosophy has been explained, we can talk about how to go about actually creating immersive game environments.

Let’s get this out of the way first; With the advance of VR and AR technologies, immersion in video games gets a whole lot easier. The applicability of what we’re about to discuss, however, is not limited to a certain technology or camera angle.

The game narrative should be about the game’s world, not the player.

To elaborate on one of the points made in this section; Players should not feel as if they are the center of the game’s world. Not every part of the game’s environment has to react actively to players’ actions during gameplay. This will subconsciously imply the fakeness of the world to the players.

If all that every NPCs ever cared about was to make you feel good (or bad!), and if every major event in that world waited on you to play a heroic part in it, then you have a major problem to make that world feel real and alive for the players.

Some events should be completely out of players’ touch or control and they should only be able to observe them. Just like in the real world.

They must see that the characters of that world have other concerns other than players’ lives and quests, they should hear them worry about this year’s harvest. Or even how they hate the snowy environment they are placed in. NPCs should have their own set of personal enemies and allies, hopes and dreams, and even their own quests.

In short: making the player feel that events in that world would go on even if he/she wasn’t there should be a goal for every game developer.

9. Setting the Mood Through Environment

Every game has some sort of atmosphere going on, even the bad ones. The biggest purpose of the atmosphere is to set you in a certain mood throughout the game. One could argue the technology worked in a game’s graphics play one of the key parts in this department and that’s not far away from the truth.

However, the color palette is arguably far more important for creating the desired atmosphere that matches with theme and story.

By supporting each other the result becomes a game world that sets you in a certain mood the moment you jump in. Even if it is about a white hair mutant whose profession is to hunt down fictional monsters and ghosts.

The Witcher 1 graphics are downright ancient at this point. But I would still feel the creeps by exploring the streets of Vizima, one of the earliest zones in Witcher. The color palette is creating this horror theme and it’s obvious that this was the intent of the developer.

While walking throughout the place you can almost feel how miserable it is to live here especially at night the only people you meet here will constantly confirm this to us.

10. Completing the Visuals With Sound

Admittedly, the sound design of a game is not an environment designer’s job. However, it is impossible to have an awesome game world without proper music and sound effects. So we will briefly discuss the profound effects of a game’s environment that is in harmony with its sounds.

Each visually distinctive part of a game environment has to be accompanied by its own complementary soundtracks. This is not the case for the games that intentionally prefer a silent, brooding mood that is in line with the rest of the game. We’re talking about horror games or the games like Inside that actively creates suspense from silence.

Imagine players hear a piece of jolly upbeat music while navigating through a dark forest at night. Needless to say, it becomes much harder for them to feel scared or worried. Hearing an eerie thrilling music score in that same forest will probably make them feel genuinely scared.

Besides the music score, the correct use of ambient environmental sounds can make or break the immersion of a game. When the players are walking through that aforementioned forest, they expect to hear the sound of dry leaves crumbling under their feet.

They expect to hear a distant owl hooting or even to hear the heavy breathing of the game’s anxious protagonist. In an urban game environment, this will translate to hearing the horns of distant cars, or the chatter of pedestrians.

Summary

Game design is an incredibly complex process. Its a process where there are lots of interactions between different parts along the way, and where every decision can have significant and often unpredictable effects on later ones.

A truly multidisciplinary field, game production has to be done through the collaboration of people from drastically different professions.

Therefore while it matters how well each part of the development process goes; It is the interaction and relation between games’ many parts that make a truly great or an awful game.

Having the best game environment design is great. But it doesn’t mean much for your game’s success if it is not in harmony with the rest of it.

Even different components of environment design itself have to agree with each other. So, the most difficult challenge when designing your game’s environment isn’t any of its’ constitutional parts. But it is to make sure every part is working in sync with each other; Working toward the same goal and vision that the game is meant to achieve.

Which games had exceptionally great or awful environments design your experience? Did we talk about it here?

Let us know in the comments below!

FAQs

How do design teams avoid confusing level layouts?

Misjudging scale early on leads to confusing environments. Set clear scope and proportions before expanding.

Why is balancing creativity and budget so tough?

Resource limits can restrict artistic vision. Strategic planning helps maintain creative flair within budget.

How are performance and immersion balanced?

Environments need optimization, like reducing poly count and compressing textures, for smooth performance.

How do teams coordinate environment art workflows?

Game environment creation spans concept, modeling, lighting, texturing, sound, and QA roles.

Why is time a major constraint in environmental art?

Creating detailed environments is time-consuming. Developers often face budget and tight schedules.

What happens when technical limits hamper creative vision?

Artistic ideas must align with engine and hardware limits, or else risk poor performance.

How do designers account for audio in environments?

Immersion grows when audio is integrated from the start. We are talking about ambient sound, footsteps, and environmental cues.

Does mismanaging project scope hurt development?

Yes. Creatively ambitious plans without a clear scope lead to cost overruns and subpar delivery.

What iterations do environments often need?

Environment designs often require multiple revisions, balancing aesthetics, usability, and performance.

Why is delivering a sense of place tricky in levels?

Strong environmental design must mesh aesthetics, gameplay, narrative, and audio to create true immersion.