Game art localization involves adapting a game’s visual elements to suit the cultural and linguistic preferences of different target markets. Ever wondered how some games effortlessly catch on with players from all around the globe, crossing cultural lines like a hot knife through butter? There’s a reason for this — lurking behind the universal appeal is a complicated process, one that transcends mere translation. Say hello to the fascinating world of video game art localization: an essential part of video game production, though one which is often perhaps unfairly overshadowed by more overtly creative or technically demanding elements.

In this expansive examination, we are unpacking the universe of designing games that are custom-made to feel as though they were made only for that player without thought to their social methodology. We will deconstruct the myths about why you can not just change that cool logo because it is not only a matter of fashion how something as simple as a color can say so much depending on the continent.

Need Game Art Services?

Visit our Game Art Service page to see how we can help bring your ideas to life!

1. What Is Game Art Localization Anyway?

We’re going to start with the fundamentals that offer some prospects. What is Game Art Localization? It is no less important than other parts of the game localization process that involve translating text, localizing audio, and tweaking gameplay elements. As a result, art localization is arguably the most conspicuous and impactful component.

If you owned a Japanese tea house, you wouldn’t serve cheeseburgers in it, would you? The art in your game works the same way. Something cool in California may be eyebrow-raising, if not worse, in Cairo. And no, this goes way beyond changing the text on some menus and some colors. That means nothing less than a full-scale revision of your visual elements, to ensure that people from other countries and cultures will feel the emotions that you intended.

Game Art Localization Revolves Around:

- Redesigning characters to better reflect local aesthetics or avoid cultural taboos

- Adjusting environmental art to match local architecture, flora, and fauna

- Reworking user interface elements to accommodate different languages and reading directions

- Modifying color schemes to align with local color symbolism

- Adapting marketing materials and promotional art for different regions.

Apart from artistic skills, this process requires understanding the local cultural distinctions and avoiding unsuitable content. Just think of one of the most popular games, Overcooked! This cooking simulation game portrays various kitchen styles from various parts of the world. However, the game’s creators made the art to be country-specific – from the pictures on the walls to the products on the shelves.

The above only refers to looking “local”, and not much else. Honestly, sometimes game art localization just means doing some cuts and a few changes within the image that may not be suitable for certain markets after all. Others are more severe, oftentimes resulting in games having to change or remove skeletons and skulls as in the case for Chinese audiences with portrayals of dead bodies being considered lazy.

At its core, game art localization aims to provide an immersive experience unique to every player, no matter where they are. It is about letting your game talk in the universal language of captivating visuals while also appreciating and celebrating cultural diversity.

2. Why Should You Care about Game Art Localization?

Hold the phone, you might ask: But isn’t good art universal? Well, yes and no. Amazing graphics may cross cultures but passing up localization is basically leaving money on the table. So let’s get straight to it: why is game art localization so important?

2.1 Expanded Market Reach

This is the big one, folks. Art that is responsibly and effectively localized can connect your game to a wider audience of players in other parts of the world, leading to increases in sales and player numbers. The global games market is huge and heterogeneous, with every region exhibiting its unique preferences and cultural differences. While your characters and environments may be much better looking for other markets; you are opening your doors to millions of potential gamers just by adapting the art in your game!

For instance, take Puzzle & Dragons. The Japanese release of this mobile game was well received, but Western audiences were less enthusiastic. Why? This is partially because the visuals went too far in an “anime” direction more cartoonish than Western tastes of the era would bear. When the art was more Westernized, the game quickly surpassed in popularity.

2.2 Cultural Sensitivity

It is very important to prevent any accidental offense or confusion as a result of culturally inappropriate visuals. Make a misstep and your game could be banned in some countries or lead to a PR nightmare. Flashback to the outcry when the Taiwanese horror game Devotion was discovered with an offending image of China’s president. Not only was the game taken down from Steam, but Respawn faced some backlash.

Conversely, cultural sensitivity is far more than a matter of avoiding offense. It is also a way of respecting and understanding the cultures of your players. This will translate to loyalty among players which means positive word of mouth.

2.3 Enhanced Immersion

The game world feels more like their own culture due to the art proliferation. This deeper immersion can result in increased time played, higher user retention – and ultimately more revenue (if that is your goal).

Think about how Assassin’s Creed meticulously recreates perspectives of history from across a range of cultures. The detailed work of environmental art in architecture, clothing, and the like makes them feel truly transported to a different time and place.

2.4 Competitive Edge

Localized art is the difference between being seen or lost within an over-saturated market. There are actually millions of games out there, so a single glance is enough to want to play or skip a game in your mind before you even land on the landing page. If the art that you make speaks to their cultural aesthetics, then you already have an upper hand in your competition.

2.5 Legal Compliance

Sometimes art localization is not about choice — it’s about law. There are some countries with strictures as to what is and isn’t allowed to have within a game One example is a long-imposed ban on any violence or offensive Nazi symbology in games, such as in the case of Germany. If you do not localize your art for those markets, it is quite possible that your game may never have the opportunity to be released on the market.

2.6 Brand Building

With a careful approach to art localization, you can cultivate an image of your brand as an internationally conscious and competent game developer. This reputation can then lead to better opportunities for further releases of the games and potential partnerships in respective markets.

2.7 Player Education

Game art localization is often useful for learning. Perhaps one of the most profound ways in which you can accurately represent different cultures through game art is that it allows players to explore, understand, and ultimately come to appreciate elements from a variety of cultures. For games where you have a particularly historical or cultural theme, it’s going to come through so much more.

3. The Items Included in Game Art Localization

Let’s get our hands dirty and dig deep okay?! Localizing game art is not a one-time process. This will affect just about all the graphics settings of your game. Below is a detailed description:

3.1 User Interface (UI)

Your game’s UI is the front of your game and must dazzle in each dialect. This includes:

Menu Design: Languages expand and contract differently. Another example would be having an English button with the word “Play” translating into German as maybe a whole sentence. This means your UI needs to be able to accommodate more or fewer words, and that might affect the layout.

Icons: Many icons have a cultural interpretation. In the US, an “OK” hand gesture is genial but in Europe and South America, it’s offensive. While a thumbs-up is a gesture of approval almost everywhere in the Western world, it can be offensive to present that sign in some Middle Eastern countries.

Fonts: Every font is not compliant with all the alphabets. Arabic, Chinese, and Korean will use completely different typefaces In addition, the fonts that look cool and stylish with Latin scripts may appear less legible or clear in other writing systems.

Colors Schemes: Different cultures perceive this in contrasting ways For instance, red means good luck in China but can also mean danger or warning in the West. You may want to change your UI color scheme if it implies the wrong thing.

Directional Indicators: You will have to flip directional arrows and readjust the flow of your UI elements in right-to-left languages (RTL) such as Arabic or Hebrew.

If you want to uncover the secret ingredients of a captivating game UI please check out Ins and Outs of Mobile Games UI Design.

3.2 In-Game Text

This is more than a word-for-word translation as you can see in the example above and we go through all 5 main steps of our strategy. Consider:

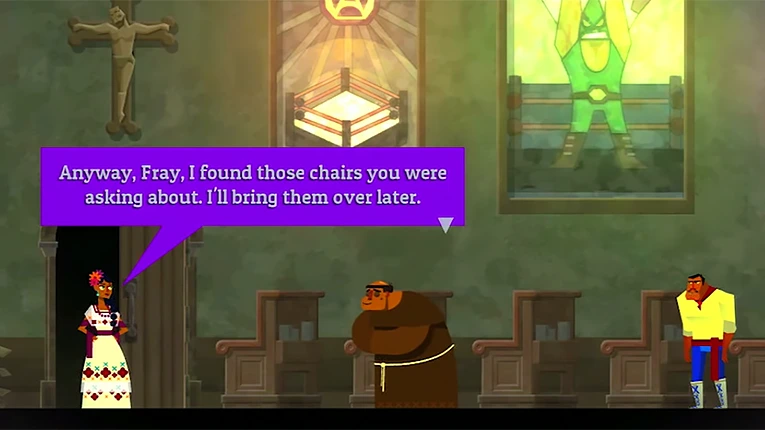

Text Bubble Sizes: This is quite self-explanatory; Japanese text tends to fit in less room than English, while German needs more. Text boxes need to be able to handle these varying lengths without ruining the layout of your game.

Reading Direction: Arabic and Hebrew are right-to-left languages, so your entire layout must flip. This includes text, as well as things such as the placement of character portraits in a dialogue scene the direction of comic-style panel layouts, or a scroll flow.

Font Choices: a font may look great in English but be unreadable in Russian or Greek. In extreme cases, you may have to commission or buy fonts specifically for certain languages.

Text Rendering: Text Rendering: Especially in languages with non-Latin scripts or anything written in a formal calligraphic system, you may need some specialized approaches to allow the text to actually display properly, particularly when it comes to typography.

Numerals and Date Formats: Different cultures use different numeral systems for ASCII characters and date formats. Not everyone uses Arabic numerals, and the MM/DD/YYYY date format found in the US is practically unheard of outside of that country.

3.3 Character Designs

Your game would be the heart of your characters. To make them work cross-culturally we might be looking at:

Outfit Adjustments: the cultural context of what is acceptable to wear varies greatly across cultures. It may be that a character’s costume is too casual for a certain market, or needs to be radically different from the default design in order to align more closely with local style.

Facial Features: When aspects of the face (shaped eyes, type of nose, or skin tone) change slightly in order to be seen as neutral the key. That does not mean you should stereotype, but instead that you should seek diversity and representation.

Body Language and Gestures: in some cultures, a Face that is friendly to one culture could be rude in another Idle animations (or emotes) of a character can be a tricky thing – agreeable in one culture and taboo in another market.

Names of Characters: This is stretching the definition of art, but especially for characters themself (and more so non-latin scripts), visualizing their name will be important. You may have to change some names entirely if they mean something unfortunate in other languages.

Cultural References: If the design of a character is rooted in cultural elements, you might need to adjust this to work for other areas. For example, a character that was built to be based on American football and sent abroad would change the character to play soccer instead of football.

3.4 Environmental Art

The game world your game operates in should be authentic, or at least not jarring, to most players worldwide:

Signage: As a street sign, poster, or billboard, it may need to be reinvented in its entirety. This was not only in terms of text translation but also in the context of the design style suitable for these elements at the locale.

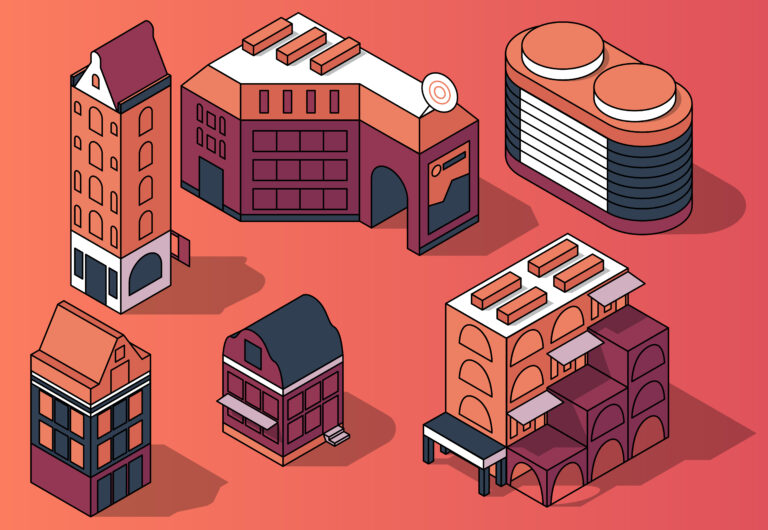

Architecture: As said earlier styles that people experience almost as second nature in a region might look completely alien to the more unfamiliar eye, meaning different takes on themes. This may require you to localize the architectural prims to coordinate with locally familiar architecture.

Biome Details: This may include the species of trees or types of weather since they can be story elements that are needed and hence might need changing to suit the world. For example, it makes no sense to place pine forests in tropical surroundings.

Cultural Symbols: This might include religious symbols, flags, or any images that hold cultural significance that would need to be inserted, erased, or altered depending on the target market

Seasonal References: Demonstrate the way seasons are appropriated in different parts of the world. Winter in a is a but Christmas-themed winter maybe, for example, hemispheres such resonate may be hime (in where December is summer).

3.5 Marketing Materials

This is the art that sells your game more than anything else, so don’t be afraid to be picky about it.

Box Art: What works in Japan may not fly so well in Brazil. So, ideally, your key art may have to be different for multiple regions.

Promo Images: Violence, sexuality, or religious imagery may be culturally inappropriate. You may need to tone down – or spice up – your promotional art according to the market.

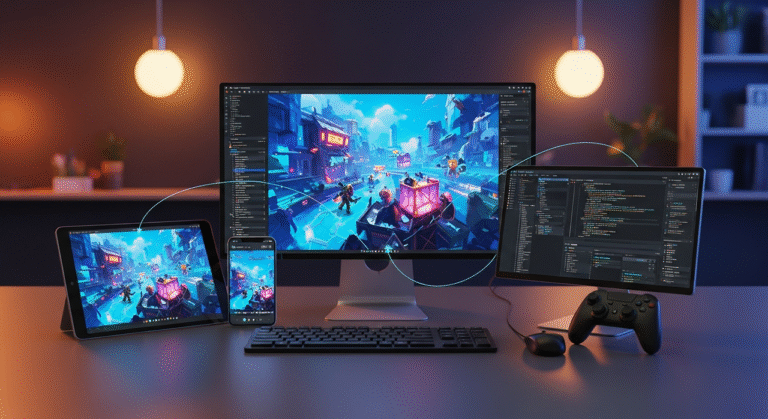

Store Screenshots: The same applies to screenshots, different markets will require completely different layouts or showcased elements. Furthermore, the devices that appear in these screenshots should closely align with whatever is trending in each region.

Logos: It could be that your game logo will need to be looked at again for other scripts. A logo that is beautiful in Latin script may become illegible when read in Chinese or Arabic.

3.6 Animation

Animation is also an area that localization can extend to, as it is often not given the same consideration as other forms or types of content that may more obviously stand to gain from alterations in translation.

- Lip Sync: If your game features a lot of voice acting where the face is visible, you should adjust the “talking” animations in scenes according to the target language, otherwise, it might just look ridiculous when your characters talk!

- Cultural Gestures: As mentioned earlier, animated gestures might need to change for different cultures.

- Pacing: Some cultures prefer faster-paced or slower-paced animations. You might need to adjust the timing of your animations for different markets.

3.7 Special Effects

Even your game’s special effects might need localization:

- Color Symbolism: The colors used in magical effects or explosions might carry different meanings in different cultures.

- Symbolic Elements: Certain symbols used in special effects (like pentagrams or yin-yang symbols) might have strong cultural or religious significance in some markets.

By paying attention to these elements, you’re not just translating your game – you’re truly localizing it, creating an experience that feels tailored to each player’s cultural context. Remember, the goal isn’t to create entirely different games for each market but to make thoughtful adjustments that enhance the player’s connection to your game world.

4. The Localization Process: From Concept to Rolling Out

Now that we know what needs localizing, let’s walk through how it actually happens. Spoiler alert: it’s not just a last-minute paint job.

4.1 Planning Phase

The best localization starts before a single pixel is drawn:

- Market Research: Understand your target markets. What are the cultural norms? What are the taboos? This isn’t just about reading a few articles online. Consider hiring local consultants or partnering with regional game studios to get insider knowledge.

- Style Guide Creation: Develop a flexible art style that can adapt to different cultural contexts without losing its core identity. This guide should include not just color palettes and character design principles but also notes on how these elements might need to change for different markets.

- Asset Management Plan: When globalizing software you may be using some sort of localization management software or even a custom database. The crux of the issue is having a workflow that can support updates and version control for many localized versions.

4.2 Creation Phase

Keep localization in mind from the start as your artists bring the game to life.

Layered files: Create art assets in layers so text and other elements can be swapped out easily Important token for anything with a letter on it – e.g. UI elements or runtime art, embedded text, etc.

Culturally Neutral Foundation: Begin with a design that is not too culturally embedded, then incorporate elements of localization. This can save you a lot of time and resources in the future.

Vector graphics (SVG): Use SVG for icons and other UI components when applicable. These images are resizable without losing quality, for when you need your content translated to a language that takes more or less space than your default language.

4.3 Localization Phase

This is where and when the magic truly starts to happen.

Cultural Consultation: Work with experts from your target markets to bring potential problems up front. This could take the form of key informants, online surveys, and/or even working with local game developers.

Cultural art adaptation: Create new designs on the basis of cultural feedback. This could amount to everything from color swaps to full character overhauls. Expect some revisions, more likely numerous rounds.

Integration of Text: Include translated text and modify layouts as required. This often demands a lot of close coordination between artists and UI designers to make sure everything fits well and looks nice.

Contextual Review: Do localized art assets carry on convincingly and naturally into the main game? Change is sometimes good on paper, but when it comes to actual gameplay, it falls flat.

4.4 Quality Assurance

Never skip this process unless you want to be a cautionary tale on some game dev forum.

Cultural Playtest: You can also let your game be played by native speakers and cultural experts. Find anything that seems out of line with good taste.

Technical Check: Ensure all localized art displays correctly across different devices and resolutions. This is particularly important for mobile games, where screen sizes can vary dramatically.

Consistency Review: Keep an eye on all those localized elements as one combined piece of your game. When you start to make changes for more than one market, it’s tempting to let things become fragmented and unrelated.

Performance Testing: Be sure your localized art assets do not affect the performance of the game. This is extra important if you have to add some new fonts or grow your texture realm due to new languages.

4.5 Launch and Beyond

Meaning, your work does not end when the game is live in the store!

Listen to Community Feedback: Notice the reaction of players in certain regions to your art. Feedback from social media and game forums can be very helpful.

Continuous Updates: and plan to continue making changes based upon player feedback or shifting cultural attitudes. The game industry works quickly, and something that is safe today might not be tomorrow.

Seasonal Content: If you are planning to do updates based on seasons, holidays or other special events just remember those change depending on where your audience is located. Consider this when planning your art updates.

5. Game Art Localization: Essential Software

And sure you would not decide to build a house with only a hammer, correct? Game Art Localization Applies The Same. Some tools to reduce the hustle:

Adobe Creative Suite: The go-to tool for building visual representations of all shapes and sizes. These tools are very beneficial in game localization as illustrated by programs such as Photoshop, Illustrator, and After Effects.

Unity Localization Package: Awesome for managing localized assets in Unity projects. Switching between localized assets should be smooth, and the library also provides support for right-to-left languages.

Unreal Engine Localization Dashboard: This one is for developers using Unreal and aid in organizing localized assets and text.

Crowdin: This is a Translation Management Platform and It can do a bit of visual assets localization as well. Great for working with a team of translators and localizers.

GitLocalize: This offers a native integration of localization in your Github workflow that is perfect for when you need to have up-to-date localized assets with corresponding main development code.

PhraseApp: Another full-stack l10n platform supporting a broad spectrum of file formats and good interfacing with disparate development workflows.

Texture Packer: Creates and manages sprite sheets for 2D games that are a must-know when working with critical 2D localization of any games.

Lokalise: Provides visual context for translations – which can be super convenient when UI localization is concerned. It also has support for other file formats which are used in game development.

That being said you know the best tool is the one that suits your workflow. Don’t hesitate to combine or even create your own solutions. Most of the biggest game studios have their in-house localization tools built exactly as they need them to be.

6. Mistakes You Could Make (And Should Be Aware of)

Paying attention to mistakes others have made can keep us from making them ourselves. Check out some typical translation mistakes and how to avoid them:

6.1 The "One Size Fits All" Approach

Never assume what worked in your home market would necessarily work in any other market, that could lead to disaster.

How to avoid it: Do your homework. Study each target market in depth, and prepare to adjust greatly if necessary. Try creating “personas” for your average player in each market to help steer your decisions.

6.2 Visual Metaphor Literal Translations

But visual puns or metaphors are a whole other game. There have been times when a character looked “cool” to one culture but was off-putting in another.

How to Avoid It: Utilize local artists or cultural consultants to identify alternative, culturally relevant visual metaphors within each market. In some cases, it might make more sense to simply develop new imagery instead of forcing a connection.

6.3 Ignoring Cultural Taboos

In other words, what is considered alright in one culture may also certainly be considered an insult in another. Or how everyone lost their minds after a Taiwanese horror game called Devotion used an image that mocked the Chinese president? Steam pulled the game, and the studio took a huge amount of shit over it.

How to Avoid It: Get a variety of people to look at your artwork, and tap some experts in target culture. Put together a “sensitivity checklist” for each market to make sure you are not inadvertently pushing the language/behavior envelope.

6.4 Ignoring Technological Constraints

Designing well-localized art is fantastic until it bogs down performance on local devices.

How to Prevent It: Ensure that the localized art is tested on the devices that are most popular within each region, rather than just high-end phones or PCs. Then, if you need it, get ready to reduce the quality of your art and other assets for less-powered devices.

6.5 Ignore Right-to-Left Languages

Arabic and Hebrew often require mirrored layouts, not just translated text.

The Fix: Plan a flexible UI from the beginning. Explore modular designs that can be flipped/rearranged. Test your layouts with right-to-left text at an early stage of developing your application.

6.6 Overlooking Color Symbolism

Different cultures see colors completely differently. Something that is lucky in one country, might be a sign of death in another.

How to Prevent It: Explore color meaning in the markets that you are targeting and change your color palette. If required, you can also think about creating different color palettes for distinct regions.

6.7 Believing That Every Culture Uses the Same Symbols

In some ways, symbols cannot be understood universally in your home market. This might not even make any sense or have bad meanings.

Prevention: Review the symbols/icons you use in the game. You may want to make dictionaries of symbols for each market, to state what kind of symbols are ok and which need to be swapped.

7. The Future of Game Art Localization

The art of localization changes as much as the gaming industry itself. Be sure to check out the following trends.

AI-Assisted Localization: Situational awareness is improving in machine learning. AI tools can assist in streamlining the localization process but are far from being able to replace human expertise, particularly for UI layout adaptation or initial cultural sensitivity checks.

Hyper-Localization: Now, certain games are actually reaching further than the general culture, and aiming for specific cities or areas even over just a general culture….to a degree that a game where the street art is not a far cry (almost) from your local area would become common.

Localizing in a Player-Driven Perspective: Localization is now becoming a community-based effort. A few games are playing around with tools that would let players create localized art assets the way modding communities do.

Augmented Reality Integration: Since AR games have grown in popularity, we can expect some difficulty with mixed-reality art localization. How do you create AR elements that blend naturally into varied real-world environments? This could mean creating AR assets that adjust on the fly to the player’s nearby surroundings.

Cultural Fusion: As the world becomes more connected through international audiences, the aesthetics of a few games that manage to blend cultural advantages create some interesting fusions. This same method of “global culture” seems to be a very interesting alternative to the usual localization path.

Real-Time Localization: With cloud gaming and streaming technologies advancing, in the future, we might see real-time art localization where game assets are swapped on the fly depending on your location or preference during play.

Localization for Accessibility: With games moving ever closer to being more inclusive, we might be on the cusp of seeing more crossover between accessibility and localization. This could mean making alternate art assets for different cultures, indeed, but it also can mean for players with a range of visual modalities.

8. Wrapping It Up: The Art of Balance

Ultimately, game art localization comes down to a balancing act. You are certainly skating a fine line between preserving the artist integrity of your basic game and trying to make it culturally relevant to its players at large. It is not an easy job for sure, but when you do this right you can make your game a global phenomenon.

Don’t forget, that localization is not only limited to being sure you do not generate offense (though that is important). They are really about intimacy. Art that speaks in a direct way to our collective, everyday, lived cultural experience will help your game cross over in the minds of players from being a foreign import to becoming another familiar window into their world.

In short, as you begin your quest to set, also be willing to try new things. Instead, use the diversity as an inviting challenge to allow your game to speak not just through its mechanics or story, but wherever a pixel or brush stroke lives.

Look at Pokémon for a success story — with its creature designs crafted to appeal to any market — or the persnickety cultural craftsmanship of Assassin’s Creed’s recreation of historical settings from across time and space. These games are not simply translated — they resonate internationally.

But also take a lesson from the blunders – remember all that uproar when Winning Eleven (Pro Evolution Soccer) had an Islamic call to prayer as one of its music tracks? Things like Fallout 3 being censored to the max in Japan with a mission involving nukes? The previous examples are only two of the means by which culture should be considered with respect to a game, within and including its visual art;

Moving forward, make an effort to assemble a team of different cultural backgrounds that can help refine your art from the very beginning. Develop local artists and cultural consultants in your target markets. And, most of all, operate from a place of wonder and dig into the amazing patchwork of human civilization.

Besides, if gaming culture is truly getting smaller and regional differences are lessening in this increasingly global industry, the biggest games won’t just play across the globe – they’ll feel like a part of it. Now, dear devs, this is the real art of game localization.

So get out there, make some games the world has never seen before, and let your game’s art blow every one of the players’ minds.