Game narrative design is the art of seamlessly weaving story and gameplay into a single, cohesive experience. Unlike passive media like film or literature, games transform the story into an interactive, dynamic journey.

Masterful narrative designers must possess a deep understanding of not just storytelling, but also level design, player psychology, and pacing.

From sprawling AAA games like The Last of Us to celebrated indie masterpieces such as Hades, every truly successful game art studio expertly blends narrative with mechanics to engage players on both an emotional and intellectual level.

In this guide, we will break down the major principles, methods, and tools you need to create compelling, player-driven stories that succeed in today’s market.

What Is Game Narrative Design?

Narrative design is the blueprint for how a game’s story will be delivered through its gameplay, dialogue, environment, and player choice. It’s an art beyond writing animation scripts; it’s about designing holistic experiences where the story naturally unfolds as the player interacts with the world.

Narrative designers work in close, critical collaboration with writers, level designers, and gameplay teams to ensure there’s complete consistency between the mechanics and the storytelling. For example, in the classic BioShock, the unique setting and the player’s actions perfectly reinforce the story’s deep moral themes.

The ultimate goal is to generate profound emotional immersion, ensuring players feel like active participants in the story, not just distant observers.

What Makes Writing for Games Unique? The 5 Key Aspects!

Writing for games isn’t the act of telling a fixed story; it’s about guiding a story that the players themselves have the power to shape. Unlike linear media, games demand flexible narratives that fluidly respond to player decisions, pacing changes, and core gameplay loops.

Game writers must constantly think in terms of branching dialogues, replayability, and nuanced environmental storytelling. A truly strong game narrative will evolve organically with the player’s actions, rather than attempting to rigidly dictate them.

Let’s dive into five key considerations that make game writing uniquely complex and creatively rewarding.

Match the Story with the Game, Not Vice Versa!

Your narrative must fundamentally serve the gameplay, never the other way around! If you are writing for an intricate puzzle game, a sweeping political drama might feel jarring and misplaced, whereas a clever mystery could fit perfectly.

The narrative’s primary function should be to enhance what players are already enjoying doing in the game. Consider Portal; its smart story brilliantly reinforces the core mechanics and distinct tone of experimentation. Always ask yourself: “What emotion does the gameplay evoke, and how can my story powerfully amplify that feeling?”.

Don’t Fall in Love with Your Story!

Game narratives are inherently prone to change as the development process evolves. Mechanics shift dramatically, levels are sometimes cut entirely, and pacing adjustments often necessitate radical changes in storytelling.

Writers who cling too tightly to their original drafts run the risk of irreparably breaking the player experience. Flexibility is key! Great narrative designers are masters at adapting their stories to support gameplay evolution, just as the The Witcher 3 writers did when the core quest flow had to be adjusted mid-development.

Good Game Stories Are Flexible!

Unlike film, games inherently demand modular storytelling. Players have the freedom to skip dialogue, explore areas out of the intended order, or completely ignore side content.

Your narrative must be robust enough to withstand these variations.

Nonlinear design, such as Skyrim or Disco Elysium, grants players meaningful freedom while consistently maintaining emotional coherence. Build adaptable storylines that remain compelling and engaging even when they are encountered in a fragmented way.

Start Your Game Story with a Single Emotion!

Before you write a single word of script, make a definitive decision on how you want players to feel. Is it fear? Wonder? Fierce determination?. This crucial emotional anchor should then shape every subsequent design decision, from the art direction to the specific gameplay mechanics.

Celeste is a perfect example: every single jump and struggle in the platforming reinforces the central emotional theme of perseverance. Starting with a clear emotion ensures that every story beat and every gameplay loop works in perfect harmony.

Experiment Before Committing!

Prototyping isn’t just a step for mechanics; it’s vital for your narrative, too. Test your story’s concept art early through dialogue samples, simple branching scripts, or even basic storyboards. See how the narrative feels in the context of play.

Narrative experimentation will help you avoid costly rework later and will often reveal which story moments resonate most deeply with players. Innovative games like Undertale and Outer Wilds refined their most powerful emotional beats through rigorous early iteration. Don’t wait until it’s too late to fully test your story’s impact.

What Are the Three Pillars of Game Writing? The Holy Trinity!

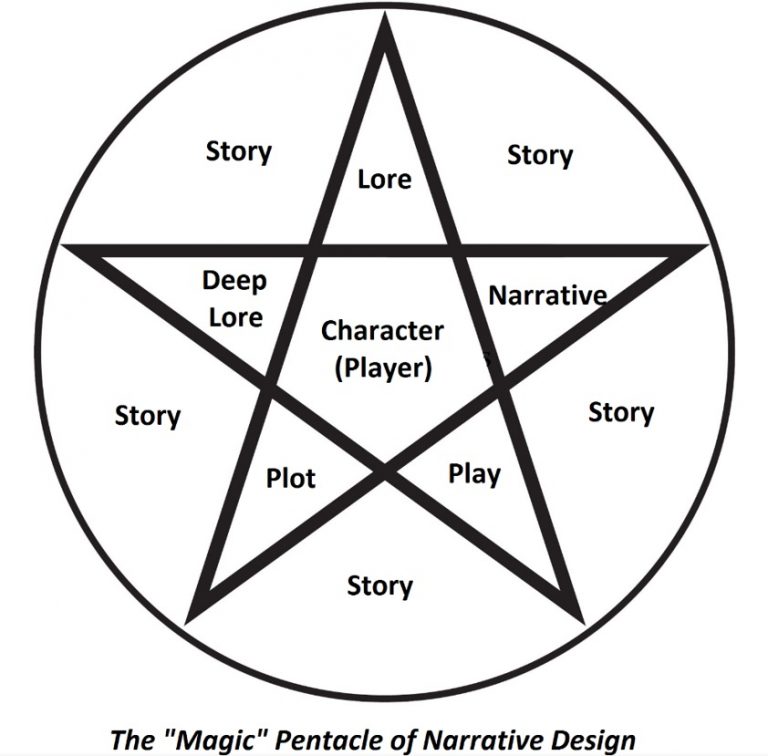

Every truly strong narrative in the game design process rests on three fundamental pillars: Plot, Character, and Lore. Together, they form the “Holy Trinity” of game writing, a cohesive framework that perfectly balances action, emotion, and worldbuilding.

Plot drives the player forward, characters forge a vital emotional connection, and lore builds deep immersion. Without harmony among these three essential elements, even the most polished gameplay can ultimately feel empty and hollow.

Plot

The plot is the backbone of progression: the logical chain of cause and effect that consistently keeps players moving forward. In games, plot is typically segmented into clear missions, levels, or quests that must fluidly align with player actions.

A well-designed plot feels genuinely reactive, never arbitrarily imposed. God of War (2018), for instance, perfectly aligns its central journey with a deep arc of emotional growth, expertly using gameplay to mirror the narrative stakes.

Characters

Characters are the emotional core of any narrative. They imbue challenges with meaning and powerfully reflect the consequences of the player’s choices. Unlike in passive media, players inhabit these characters, often forming profound, deep emotional bonds.

Memorable examples of great game character design include Ellie in The Last of Us and Geralt in The Witcher 3. A well-written character evolves meaningfully alongside the player’s journey, blending scripted arcs with vital interactive moments.

Lore

Lore is the soul of the world: the myths, histories, and cultures that make the setting feel alive and tangible. Good lore is presented in a way that invites exploration rather than dull exposition.

In Dark Souls, crucial story details emerge through cryptic item descriptions and subtle environmental cues, serving to deeply reward curiosity. Thoughtful lore transforms a simple map into a living, breathing universe that players are eager to uncover.

How Do You Create the Three Pillars of Game Writing?

Building a cohesive narrative system requires you to align your plot, characters, and lore under one unified thematic vision. Let’s break down how to effectively craft each element for maximum immersive storytelling.

Crafting a Player-Driven Plot

Begin by clearly defining the player’s fundamental core goal, conflict, and motivation. Every single gameplay loop should consistently tie back to these foundational narrative anchors.

Use intelligent branching storylines or dynamic objectives to sustain player engagement. Games like Mass Effect brilliantly demonstrate how player choice can redefine plot outcomes while masterfully maintaining narrative coherence.

Building Resonating and Interactive Characters

Design your characters with both a critical narrative purpose and a tangible gameplay function. Ask yourself: What does this character teach the player?. How do their personal goals align with or conflict with the core gameplay?.

Smart dialogue systems, moral choices, and advanced companion AI (as seen in Red Dead Redemption 2) are all key tools that help players form authentic, lasting connections.

Developing Lore That Feels Alive

Treat lore as an interactive experience, never as a dry lore dump. Embed it subtly into the level design, specific item descriptions, and optional side quests.

Subtle storytelling, like in Hollow Knight, strongly encourages discovery and personal interpretation.

When players are able to piece together the lore on their own, it fosters a profound sense of ownership and genuine wonder.

Use a Story Bible to Keep Track of Everything!

A Story Bible is your narrative command center! It is a living, breathing document that meticulously organizes every single detail of your world, characters, and storylines. It is essential for ensuring team-wide consistency and preventing continuity errors as your game inevitably evolves.

In large-scale productions, it acts as the single source of truth for designers, artists, and programmers alike. Modern studios such as CD Projekt Red and Naughty Dog maintain comprehensive story bibles to align narrative tone across expansions, DLCs, and marketing materials.

Keeping an updated Story Bible helps your narrative smoothly scale from the initial concept all the way through to post-launch support.

Final Words

Game narrative design is the ultimate bridge between art and interactivity. It is the powerful space where mechanics, story, and emotion converge to forge truly unforgettable experiences.

By carefully aligning your story with gameplay, mastering the Holy Trinity of Plot, Character, and Lore, and diligently maintaining a clear story bible, you establish the foundational structure for immersive storytelling that players will cherish and remember. Ready to elevate your storytelling to the next level?

FAQs

How to make a video game plot?

Start by outlining the main storyline, define key events and endings, then map character arcs and arcs to gameplay flow.

How to write lore for a game?

Begin with personal inspiration and world visuals, then write beyond the game. You can use moodboards, comics, and extra text to enrich lore.

How is narrative design different from game writing?

Writing crafts characters and dialogue. Narrative design structures a story through player interaction, pacing, branching choices, and tone.

What does a narrative designer do daily?

They map story flows, design dialogue systems, integrate audio and visuals, and ensure narrative coherence across gameplay.

How does narrative design handle branching storylines?

Designers build multiple paths that align with player expectations and choices to keep the story engaging.

Can narrative design include nonlinear storytelling?

Yes. Narrative design often enables nonlinear or branching structure, adapting story flow to player choices.

Is narrative design a recent game discipline?

Yes. It’s a young field, first emerging around 2006, and still evolving in techniques and expectations.

Do narrative designers afford creative freedom?

They must balance creative vision with mechanics to guide player emotion and maintain narrative integrity.

What skills do narrative designers need?

Storytelling, systems thinking, collaboration, and understanding of game mechanics and player behavior.

5 Responses

Glad you liked it 🙂

Thx Maria, We have all sorts of cool posts coming up, make sure to check back soon!

I truly appreciate this article. Thank you!

You make a solid argument! Do u have anything about the relation of Narrative Designers with the rest of the game development team?

I believe this post could have what you’re looking for.

Cheers!