Psychology studies behavior and mental processes, how a subject may react or process an emotional event regardless of whether the subject is a human or animal. It does have many subfields and various schools of thought. The impact of psychology on the animation production pipeline is significant as it influences various aspects of the creation process. Understanding psychological principles helps animators create more relatable and emotionally resonant characters, enhancing audience engagement.

The question is, How do animators and animation companies benefit from this branch of philosophy? And How do they actually implement psychology into animation?

In this article, we will discuss various methods and theories of psychology used in animation and how this knowledge is used in different steps of animation production like character design, storytelling, concept art, visual communication, and even sound and music of an animation.

Need Animation Services?

Visit our Animation Service page to see how we can help bring your ideas to life!

I- Pre-Production

In the pre-production stage of any animation service, there are 3 main components: creating concepts, script writing, storytelling, and color script. Let’s see how psychology affects each step.

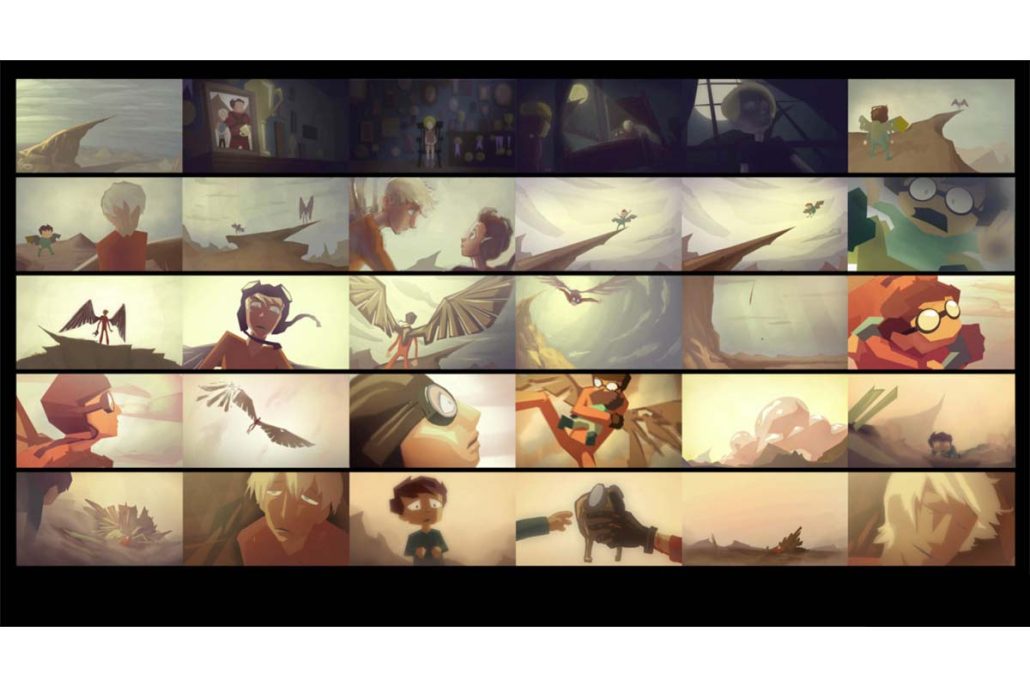

I-I Concept Art:

Concept art will dictate the style and overall look of any animation. This is where artists will use uncanny valley theory, which suggests that humanoid objects that imperfectly resemble actual human beings provoke uncanny or strangely familiar feelings of uneasiness and revulsion in observers. “Valley” denotes a dip in the human observer’s affinity for the replica, a relation that otherwise increases with the replica’s human likeness.

We can see clear examples that use said theory in animations like Inside Out, Elemental, Zootopia, The Bad Guys, etc., where the designers give humanoid features to increase viewer engagement and overall empathy for the characters and their world.

I-I Concept Art

Ray tracing is considered one of the most advanced rendering techniques. By simulating the path of light rays as they bounce around a scene, ray tracing achieves remarkable realism in reflections, refractions, and lighting interactions.

While this technique yields astonishingly lifelike visuals, it demands significant computational power and is often used for pre-rendered or high-quality animations.

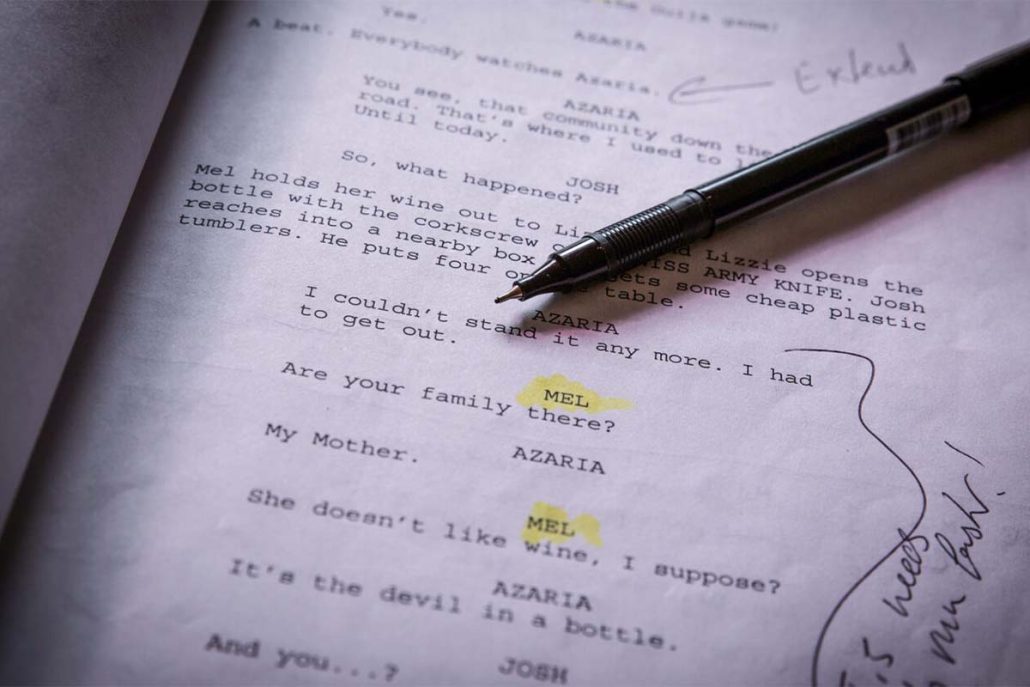

I-II Script Writing and Story Telling

Scriptwriting refers to writing the screenplay, the written dialogue, and scene descriptions that provide the narrative blueprint for the animation. The script outlines the characters, settings, actions, dialogue, and plot progression.

There is some overlap between scriptwriting and storytelling in animation, but they are not exactly the same thing.

Storytelling is a broader process of determining narrative elements like themes, tone, pacing, story structure, character arcs, etc. Everything conveys what the story wants to tell the audience.

This is the stage where psychology plays a big role in animation. Psychology is unwrapping different perspectives and a story is exactly a perspective toward a subject.

In order to grab the attention of the viewer, any story needs questions or a tangible subject. You don’t always have to answer that question or clarify the subject as the writer of a story, but having a subject or base question is a must!

We can take a look at Soul, produced by Pixar Studios, as an example. This animation explores the subject of identity and purpose. The topic is suitable for adults and the animation and events embedded in the animation are suitable for the children, the perfect family show!

Let’s look at another thesis, Chekhov’s gun. Chekhov’s gun is a dramatic principle that states that every element introduced in a story should serve a purpose. The name comes from a quote by Russian playwright Anton Chekhov:

“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off. It’s wrong to make promises you don’t mean to keep.”

In other words, don’t include any unnecessary details in a story. All elements, characters, props, scenes, dialogue, etc., should contribute meaningfully to the plot or themes. Anything irrelevant should be removed.

A lot of animations use this rule by using easter eggs that are found mainly after some time has passed from the initial release of an animation. We can always see that some scenes that at first glance felt insignificant have a little secret hidden inside them. For example, we can mention Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, which had the wolf appear in some shots that we didn’t even see on the first watch.

Another theory that is worth mentioning since adult animations keep dragging more audiences is the Incongruity theory.

Incongruity theory posits that humor and laughter often arise when there is some kind of discrepancy or inconsistency between what we expect to happen and what occurs. The surprise factor of something being different from normal patterns, logically inconsistent, or incompatible with our assumptions elicits amusement and delight. Adult animated shows leverage incongruity theory heavily for comedic effect.

Shows like Family Guy and Rick and Morty create humor through the unexpected by deliberately subverting predictable genre conventions and narrative tropes. Characters find themselves in absurd situations that violate behavior, physics, and rationality norms incongruities with the typical cause-and-effect we expect from reality. Outlandish personalities generate laughs because their eccentric behaviors mismatch our assumptions.

There’s a lot we can discuss here as we have many theses and theories in psychology regarding how a story can be told and what our approach toward telling a story, from a painful point of view, an exaggerated one, or a joyful and non-harmful way.

I-III- Color Script

A color script is a blueprint that concept artists create to plan out the color palette and schemes for an animated film or TV show. The color script determines how color will enhance storytelling, convey emotion, and bring scenes to life visually.

Various theories discuss colors and how they affect the viewer. We will discuss some of them in the following:

I-III-I Affective Valence Theory:

The Affective Valence Theory demonstrates that colors have an intrinsic emotional psychology beyond aesthetic appeal. Research shows warm hues like red and yellow possess positive valence and feel exciting, passionate, and uplifting.

Cool hues like blue and green have a more calming, tranquil effect associated with relaxation or melancholy. Bright and saturated colors evoke optimism and intensity, while dark shades convey mystery and sophistication.

I-III-II Activation Theory

The Activation Theory examines how color attributes like brightness, saturation, and hue affect psychological arousal and stimulation levels. There is much research regarding the fact that colors influence one’s mood and emotional state.

In a color script, the Activation Theory can help use color intensity to evoke responses from the audience.

I-III-III Mood Congruence Theory

Mood Congruence Theory is a psychological concept that suggests that people tend to remember information and experiences that are congruent or consistent with their current mood or emotional state.

In other words, when you’re feeling a particular emotion, you’re more likely to remember or be influenced by things that match or align with that emotion. This theory has applications in various fields, including psychology, marketing, and even in creating color scripts in animation.

A color script can benefit from the said theory by representing or planing outlines of the color scheme and mood for different scenes or sequences in an animated film or project. It helps set the emotional tone of the animation and guides the audience’s emotional response.

I-III-IV- Gestalt Similarity Law

The Gestalt Similarity Law is a fundamental principle in Gestalt psychology, a school of thought that focuses on how humans perceive and organize visual information. According to this law, elements that are similar in one or more ways tend to be grouped together perceptually.

This similarity can be in terms of color theory in art, shape language, size, texturing, or other visual attributes. In the context of color scripts in animation, the Gestalt Similarity Law can significantly impact how viewers perceive and interpret the visual elements presented in a scene. And how an artist will dictate the colors of a scene.

II- Character Design

A character is the face of an animation. You might even remember a certain character and not the name of the animation it was in.

But how exactly do we combine psychology and artistic values to create a character?

Let’s start with the base of any character. It’s personality. Different personality groupings like MBTI or Enneagram of Personality greatly help us design characters based on certain descriptions. Different personality types are even bound to certain visual features. If we choose a personality type for our character, we have a much easier task to translate that personality to facial features or even clothing choices.

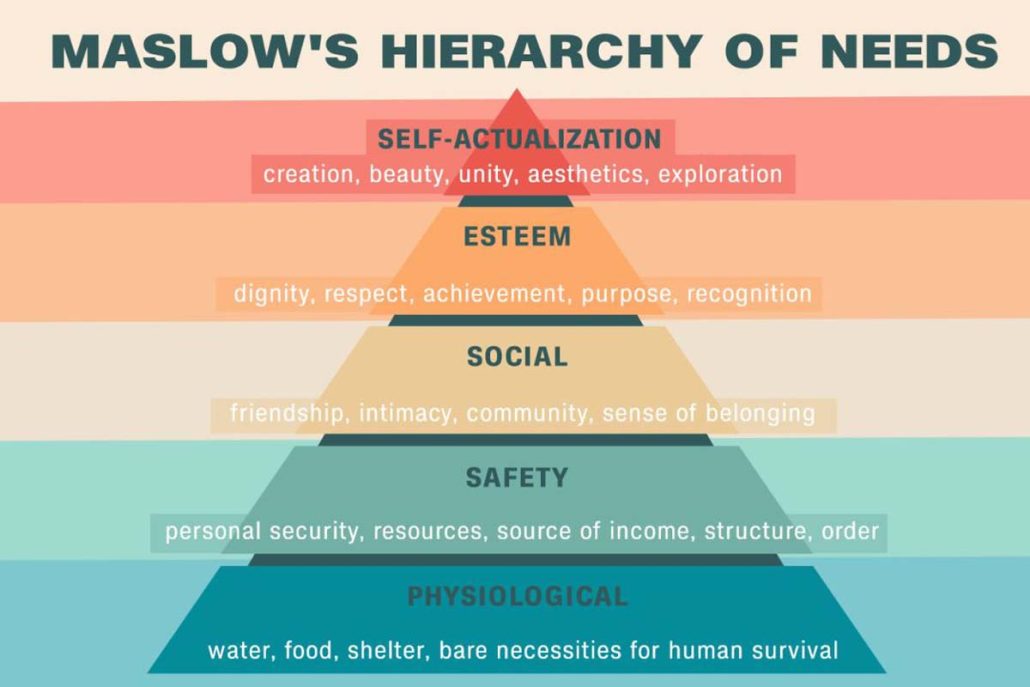

Furthermore, while we are creating any character, there is a need for motive. Why does the character do what he does? Why does he speak and behave in a certain way? We can answer these questions by getting the help we need from Character archetypes and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Character archetypes, and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs are two powerful tools that writers and creators can use in character design to create well-rounded, relatable, and compelling characters. Let’s explore how these theories can be applied to the character design process:

II-I- Character Archetypes

Character archetypes are universal, recurring patterns or roles found in storytelling across cultures and time. They draw on the collective unconscious, as proposed by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, which suggests that certain symbols and themes are ingrained in the human psyche. Here’s how some common character archetypes can be used:

II-I-I Protagonist Hero

The protagonist is often the central character whose journey the story follows. They embody bravery, determination, and a desire to achieve a significant goal. The hero archetype represents the innate desire for growth and self-actualization, aligning with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

II-I-II- Sidekick

The sidekick is a loyal and supportive character who complements the hero’s strengths and weaknesses. This archetype represents the concept of companionship and belonging, as people naturally seek social connections and a sense of community.

II-I-III- Mentor

The mentor is a wise and experienced character who guides and teaches the hero. This archetype reflects the need for guidance and self-improvement, as individuals often seek knowledge and self-fulfillment to reach their potential.

II-I-IV- Villain

The villain is the antagonist who opposes the hero and represents various negative qualities or forces. This archetype taps into the darker aspects of human nature, including the desire for power, control, and self-preservation, which can be related to the lower levels of Maslow’s hierarchy, such as safety and physiological needs.

By using these archetypes, writers can create characters that resonate with the audience’s subconscious desires and fears, making the story more engaging and relatable.

II-II- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs:

Abraham’s hierarchy of needs is a psychological model describing the stages of human development and motivation. It is often depicted as a pyramid with five levels, from basic physiological needs at the bottom to self-actualization at the top.

Character motivations and arcs can be aligned with these needs:

II-II-I- Physiological Needs

Characters might start their journey struggling to meet basic survival needs such as food, shelter, and safety. Their initial motivations could revolve around securing these necessities, and their character arcs may involve overcoming these challenges.

II-II-II- Safety Needs

As characters progress, they may seek safety, stability, and protection. Their motivation might involve forming alliances, building defenses, or finding a safe haven. Overcoming threats to safety can be a central part of their character development.

II-II-III- Love and Belongingness

Characters can experience a deep need for love, friendship, and belonging. Their motivations include forming relationships, seeking acceptance, or connecting with others. Character growth may involve addressing issues of trust, betrayal, or loneliness.

II-II-IV- Esteem Needs

Esteem needs involve gaining self-respect and the respect of others, as well as achieving personal goals and recognition. Characters may strive for success, recognition, and mastery in their chosen fields, and their arcs may revolve around self-confidence and self-worth.

II-II-V- Self-Actualization

Characters reaching the pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy are driven by self-actualization, which involves realizing their full potential and pursuing personal growth and creativity. This stage can lead to profound character transformations as they pursue their true purpose and meaning in life.

Incorporating Maslow’s hierarchy of needs into character design allows creators to craft character arcs that resonate with the universal human desire for personal growth, fulfillment, and self-realization.

III- Sound Design and Music

This section is not only bound to animation. The same rules are applied to movie music, games, or any visualization with music.

As for Animation, music relies heavily on psychological research to enhance the viewer experience. Here are some of the theories used for sound design in animations:

III-I- Conditioning

Composers associate character leitmotifs through repeated pairings, like Wagner’s Siegfried leitmotif that evokes the hero. Studies show even arbitrary music, when conditioned, elicits emotions, like the Jaws theme creating tension. Disney frequently conditions musical themes to characters to implicitly prime reactions.

III-II- Expectancy Violation

Composers surprise listeners harmonically like John Williams’ unexpected dissonant chords in Joker’s theme in Dark Knight. Music cognition studies show deviating from anticipated patterns orients attention. Pixar’s Up subverts expectations, having Muntz’s sinister theme played innocuously on piano.

III-II- Peak-End Rule

Since people recall experiences by peaks and endings, composers place prominent music at the climax, like the Avengers’ bombastic portals theme. Memory studies show finale moments disproportionately color impressions. Megamind’s triumphant “High School Heroes” rock music frames the ending upbeat.

III-III- Rhythmic Entrainment

Cutting visuals to musical beats synchronizes senses like Kung Fu Panda fight scenes timed to percussion. Neuroscience finds people implicitly entrain to rhythms. Disney’s Fantasia artfully aligns animation with classical scores.

III-IV- Equilibrium Theory

Balancing predictable themes with novelty prevents boredom but doesn’t overload. John Williams repeats Star Wars motifs but adds new material. Cognition studies show information processing requires equilibrium.

III-V- Cultivation Theory

Exposure to compositional tropes builds recognition, like associating swelling strings with heartfelt moments. Over time, musical schema develops through accumulated patterns.

Conclusion

Animation leverages psychology’s insights into the human experience to breathe life into imaginary worlds. Beyond surface-level artistic choices, creators dive deep into the well of behavior, emotion, and perception to infuse their films with narrative power.

The integration of psychological principles across the production process manifests in myriad ways: archetypal characters, story structures, color scripts, and musicals. Psychology brightens the paths through which images elicit emotion, stories satisfy needs, and sound sculpts experience. With these understandings, animators transform frames into feelings and words into worlds. Their films don’t just entertain. They leave memorable imprints on the heart.

This is the magic psychology brings to animation, guiding creative vision through tested insights into the human psyche to unlock timeless and universal appeal.