Psychology plays a crucial role in character creation by helping designers craft relatable, believable, and emotionally engaging characters. You may think that creating a character is all about art and how you are able to create eye-catching and memorable characters if you are great at drawing. But that’s not all the necessary components of a character. The majority of a character’s depth is from its impact on the story and how events had an impact on it. Great stories will give you the base you need in order to create great characters.

In this article, I will unwrap how psychology will help you greatly in your journey of creating memorable characters that stand out. And how a back story can be seen from a glance at your character.

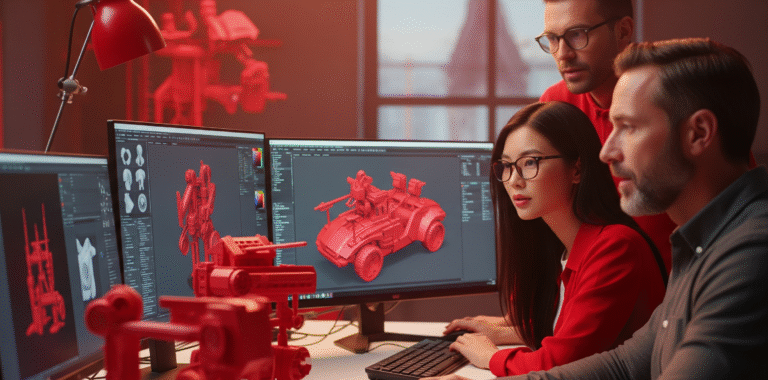

Need Animation Services?

Visit our Animation Service page to see how we can help bring your ideas to life!

I- What Exactly Can You Learn from Psychology As an Artist

I-I Non-judgmental approach

Psychologists are trained to approach people with an open and empathetic response. It doesn’t mean that the psychologist doesn’t have a personal opinion about whatever the individual may be struggling with. Instead, it means that when working with them, they maintain a balanced approach. The goal of psychology is, of course, to assist people, not judge them.

But what does this mean for writers and character design service providers? It means remembering that all people are making the best choice at the moment with the knowledge and ability that they have. This doesn’t mean that it’s a good choice (Lord knows some people and some characters make really questionable decisions), only that they’re doing the best they can. As the author or creator, you need to have empathy and understanding for what your characters are doing if you want readers to connect with those characters.

Your main character and the supporting cast will be under pressure in the animation or game. You may be killing off people who are important to them, burning down their business or crashing an asteroid into their planet. When people are under stress, they don’t always respond in the best way. If you know the core of who your characters are, it will be easier to understand how they will react in different circumstances. This helps the reader understand how the character’s goals and motivations are moving them forward in the story.

The villains in your story have their own goals and motivations. In many cases, they don’t even know they’re the bad guy as far as they’re concerned, they’re the hero. When writing your antagonist, steer away from easy answers that they’re doing something bad because they’re just bad people, or worse, that they’re doing something bad because you need them to for the purpose of the plot. Even someone who is a sociopath has their own code of behavior. They may not have empathy for other people because that’s the way their brain works, or it doesn’t work. But typically, it’s not simply a desire to be mean for the sake of being mean.

I-II How Your Character Thinks and Acts

Don’t rush to shove words and appearance traits into your characters’ mouths. Think about what they want to communicate and the words they choose to express themselves. This word choice is likely impacted by both their level of education (ambulate versus walk, periwinkle versus blue) and also their emotion (annoyance versus rage).

We’re artists; if there’s anything we should know, it’s that words and visual traits matter. Think about what words your character would choose and how their audience and their situation impact that Communication. For example, if your character is lying to someone they care about (let’s assume for a good reason), how do they speak? Does their partner notice something is off?

II- Foundation for Character Needs and Motivations

They always say that the best place to start a journey is at the beginning. A good foundation for understanding individuals and where they come from is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. I can hear a few of you groaning that you’ve heard about this theory a million times. Anyone who has taken a psychology class has likely bumped into this concept before, but stick with me. It’s well worth another look, especially for artists.

The Hierarchy is based on what motivates individuals and is most commonly shown as a pyramid with the base needs at the bottom and moving up from there. (See diagram below) Maslow started with the concept that people are motivated to achieve various needs and that some of those needs take precedence over others. That your base needs must be met first, but once those are in place, you will start looking around for the next level. You can imagine yourself scaling the giant pyramid, looking to be a more evolved person at every step along the way.

Psychologists point out that this isn’t a direct linear path you’ll bop around between the different levels, and much like many things in life, things can be flexible depending on circumstances and/or the specific individual. So instead of scaling up that pyramid, you’re far more likely to take one step forward, a step back, a step to the side, and then back up again.

While it’s a nice idea to see yourself evolving in a nice tidy linear progression, for most of us, it’s not that clear. Lastly, it’s also good to remember that people can be motivated by more than one thing at a time. Maslow’s Hierarchy is described as if a person would be at only one step at a time, and while there will be a base/focus where the individual sits, they may also have a foot on a different step.

Let’s unwrap what these 5 levels actually are:

II-I- Physiological Needs

These are the things that you need to sustain life: air, food, shelter, clothing, etc. If these needs aren’t being met, you’ve got some big problems. People are highly motivated to make sure they have these things. People who are trained to be lifeguards are warned that a drowning person will crawl up their body and shove them underwater to get their head free and breathe. It isn’t that the person they’re saving doesn’t appreciate what the lifeguard is trying to do for them, but the survival urge will kick in, and they will shove anyone out of the way to get what they need, in this case, oxygen.

Suppose you have your character in a life-or-death circumstance (i.e., they’ve been in a plane crash and are alone in a wind-swept remote portion of the Yukon miles from civilization with only torn clothing, a broken arm, a packet of peanuts, and a group of bears starting to sniff around the crash site looking for a snack). In that case, their focus must be on survival.

Threatening your character’s survival needs will engage readers because the stakes are literally life or death.

II-II- Safety Needs

Once an individual has ensured that they aren’t going to perish in the next moment, their focus will turn to safety. Safety concerns still have an element of life or death to them, but they are less immediate. Examples include protection from the elements, security, order, stability, and basic freedom to live without fear.

These needs are common in all types of manuscripts. There may not be an immediate survival need, but there are risks. Suppose your character is hunting down a serial killer, living in a refugee camp in space, or dealing with a regime overthrow in a historical novel. In that case, they are struggling with safety needs. People are creatures of routine. We like to know what to expect.

When we don’t, we can feel uneasy or unsafe. In fiction, we’re often upending a character’s life, and even what might not be a life-or-death situation may feel like one to them. Explore and consider what your character needs to feel safe and secure.

II-III- Love and Belonging

There are entire genres of books that are built on a character’s search for love and belonging. They will do what they can to reach out and find the person or people who will let them finally feel that they belong. This doesn’t mean that they won’t be independent, instead, they want to be a part of and contribute to a larger group, even if that group is only one special person.

We all want to be loved. As a writer, ask yourself who are your character’s “people?” What clues or signals would make them feel a sense of relief and welcome? What would make them feel like a fish out of water? How would they know they didn’t fit In?

II-IV- Esteem Needs

Maslow put these needs into two sub-sections. The first is esteem for oneself which includes dignity, achievement, mastery, and independence. This also includes feeling that you like yourself, that you feel good about what you can do, and while you know you have areas to work on, overall, you’re an independent functioning person. The second section is outwardly focused and includes the desire for other people to know that you’ve got your act together and things like reputation and respect.

You need to know what would make your character feel good about themselves. Is there a milestone that they need to achieve? This could be anything from having a baby to getting a particular job to moving out on their own. These milestones are often visible ways of demonstrating to ourselves that we have “arrived,” that we have reached the expectations we have of ourselves.

What do your characters like about themselves? How important is their reputation to them? It can be interesting to compare what the character assumes versus what other characters actually think of them. Do they feel their reputation is deserved? Accurate?

For example, you may have a character who has a reputation for being really successful, but the individual may feel it’s all a sham and only a matter of time before everyone finds out they don’t really have it together at all. (Ah, the dreaded imposter syndrome.)

II-V- Self-Actualization

This is the top of the pyramid! Once you’ve addressed all the other needs, you’re ready to tackle the one that can often be the most difficult. Things that are included in this section: realizing your personal potential, feeling fulfilled, and, as Maslow described, the desire: “to become everything one is capable of becoming.” No pressure or anything; just be all you can be.

There’s a reason you see people in their fifties asking themselves some hard questions. Usually, at this point, most of their base needs have been met. They have homes, relationships, and often a career that has been successful, and then they start to wonder: Is this it? They wonder what else they might be capable of doing.

Depending on the genre and the story you’re telling, your character may be struggling with this level of need. Unlike the survival needs at the base of the pyramid that lends itself well to high action and a fast plot, stories looking at this need tend to be more character-driven and internal. Nothing is blowing up, on fire, or shooting at you. This stage and, therefore, this type of story is about figuring out who you truly want to be. A great example of such a story is Bojack Horseman.

III- Backstory Basics

Psychology plays a major role in shaping a character’s backstory and motivations. When authors craft a backstory, they often consider various psychological factors that made the character who they are. For example, childhood experiences and relationships with parents often shape language, personality, and outlook.

Traumatic events may explain certain fears or obsessions of a character. The psychology of attachment theory suggests that early childhood attachments to caregivers shape an individual’s expectations in later relationships. Things like birth order and sibling rivalry can also impact personality. Self-esteem issues or perfectionistic tendencies may stem from high parental expectations during childhood. Mental health conditions like depression or anxiety may contribute to a character’s struggles. Personality traits like introversion or risk-taking may relate to innate temperament interacting with life experiences.

Specifically, authors may utilize theories like psychoanalysis to uncover subconscious drives, the effects of childhood wounds, or defense mechanisms. Behaviorism could inform how the character learned certain behaviors through reinforcement and conditioning. Social learning theory can show how relationships and environment shape the character’s development. Personality typologies like the Myers-Briggs provide frameworks for distinct personality types

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs allows writers to consider deficiencies in basic needs that may motivate behavior. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques can provide insight into how a character’s thoughts, feelings, and beliefs interact. Overall, psychology provides a rich array of frameworks, concepts, and techniques to craft realistic, multidimensional characters whose lives and choices are shaped by fundamental human needs, emotions, and cognitive processes. Writers utilize knowledge of psychology to create resonating characters whose inner lives reflect the complexity of the human psyche.

We’ve spent some time exploring character backstory and the impact that has on who they are at the start of the book and the reactions and decisions they make during the story. You now have a richer understanding of what key things happened to your character in their past and likely more empathy for who they are and some of their choices. So, what are you going to do with all of this great information? What I’m about to say may discourage you, but all this work you’ve done to think of backstory, to come up with all the sensory details… yeah, you likely won’t use all of it in your manuscript or visually show all of them in the final design.

Wait! Don’t throw your phone or laptop against the wall! That process was still beneficial. Much of this material will just be there to help you. When you’re writing, and a character faces a choice, you will have a better idea why they may do A versus B. The reader likely won’t need to know all the ins and outs, but you do. Some details of the backstory aren’t necessarily important for the plot.

For example, J.K. Rowling revealed, long after the original Harry Potter books were out, that Dumbledore was gay. This caused controversy, with some people feeling that she was in some way “messing” with characters after the fact, possibly in an effort to be more politically correct. Others felt that this was a critical detail that should have been mentioned in the story because it made them like the character more. However, since Dumbledore’s sexuality wasn’t relevant to the original story, it wasn’t included. But J.K. Rowling is clear, knowing Dumbledore’s sexuality shaped who he was and the choices he made.

IV- How This Knowledge Translates into Design

Now comes the fun part! While psychology is used in every aspect of animations or games, many might not know the impact of psychology in animation and games and how it’s used. Think about how you can actually use psychology for your designs. In visual storytelling mediums like animation, comics, or graphic novels, a character’s psychology can directly influence their visual design and styling.

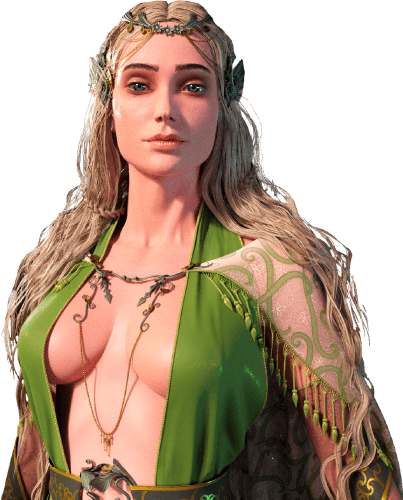

While you are starting to draw a character, you will start to think about the proportion of the character first and what shapes to use to build the body of your character. This trait of your character will come from its background and how you have created the story of it itself. Exaggerated proportions like large eyes or a pronounced scowl could signify innocence or anger issues. For example, if you are illustrating a sumo wrestler, you are very unlikely to create a skinny person unless there is an exception.

After you have your body all sorted out, you will move forward to create the facial aspect of your character, and even in that, you have to use the psychology and backstory of a character since your main goal and responsibility is to visualize a description of a character. Character design elements like clothing, hairstyles, and accessories can also convey psychological qualities – dark, tattered clothing could suggest childhood neglect or trauma. Shading techniques can portray inner turmoil or depression.

Color definition in art can reflect personality, too, with warm, bright tones for optimism versus dark, muted tones for brooding. Psychologically informed acting techniques even extend to animation. Erratic gesturing could demonstrate mania, while listless movements could show depressive tendencies.

Overall, visual design choices for characters are guided by psychological principles about how inner qualities manifest through external expression. From posture to props to movement, psychology aids artists in crafting well-rounded characters whose inner lives are reflected in their visual presentation and behavior.

Conclusion

In conclusion, psychology is the cornerstone of creating truly captivating characters. By delving into their formative experiences, innate traits, motivations, and emotions, writers and artists breathe life into their creations. Whether through words or visual representations, psychology adds depth, turning characters into multidimensional individuals instead of mere archetypes.

This profound understanding of human nature allows characters to resonate authentically, creating a connection with audiences. Through careful application of psychological principles, creators construct characters that mirror the complexities of real-life individuals, making their stories unforgettable and deeply impactful. Psychology, therefore, is the key that unlocks the door to characters who feel as genuine as the people we encounter in our everyday lives.