A well-defined game art pipeline is the foundation that transforms a creative vision into a commercially viable game, preventing confusion, repeated work, and missed deadlines.

Regardless of whether you’re a freelance artist, a small independent team, or part of a large game art studio, it is critical to grasp how 2D and 3D game art assets progress from initial concept to deployment within the engine.

In this guide, we will explore every essential phase: pre-production, production, and post-production, including a comparison of how the 2D and 3D asset flows differ practically. Let’s discuss how concept art, 3D modeling, character animation, and final integration fit together to structure your workflow.

What Is a Game Art Pipeline?

A game art pipeline is the formalized set of procedures that takes artistic ideas from the initial sketch phase to highly optimized assets ready for use inside a game engine. It explicitly dictates responsibilities (who handles what: concept artists, 3D artists, animators, technical artists), the required sequence of steps, and the specialized tools utilized.

An efficient pipeline minimizes rework, guarantees visual consistency across all assets, and confirms that assets adhere to technical limits, such as polycount, texture size, and performance constraints.

It also establishes crucial checkpoints for approvals and mechanisms for feedback between art and design teams. Essentially, the pipeline is the organized structure that ensures consistent character art, environment art, UI/UX, and VFX.

Need Game Art Services?

Visit our Game Art Service page to see how we can help bring your ideas to life!

What Are the 3 Main Steps in Game Art Creation?

Most development teams divide game art creation into three major sequential phases:

Pre-production is dedicated to setting the visual direction, art style, scope, and creating the comprehensive asset list for the video game idea.

Production is where the majority of the actual creation takes place: building, animating, and importing assets into environments like Unity, Unreal Engine, or other in-house engines.

Post-production focuses on final refinement, optimization, and last-minute VFX or UI adjustments, often leading up to the game’s launch.

How Does Pre-Production Shape the Game Art Pipeline?

Pre-production in game art lays the essential groundwork for your entire 2D or 3D pipeline. Let’s break down the key pre-production stages one by one:

Concept Discovery and Visual Research

Concept discovery and visual research involve exploring the game’s core visual identity before committing to final designs. Artists and art directors study game art trends and gather visual references from various sources (existing games, films, and fine art) to establish the desired mood, genre feel, and visual tone.

The process often involves generating concept art with loose sketches, testing character color palettes, and creating simple thumbnails to quickly evaluate ideas without sinking time into full production-ready assets.

This stage is highly iterative, seeking out strong silhouettes, memorable shapes, and clear visual hierarchy to support gameplay and player readability. For instance, enemy units must be instantly distinguishable from allies.

Defining the Art Style

In the art style guide stage, vague ideas are formalized into concrete rules that every artist must strictly follow to properly choose the best art style.

This guide documents criteria such as line weight (2D), the required level of realism (3D), precise color palettes, lighting mood, material definition guidelines, and expected texture detail.

It typically includes specific “dos and don’ts,” approved example characters, environmental examples, UI mockups, and examples of correct versus incorrect implementation.

Technical specifications, including target resolution, approximate polycounts, and acceptable texture sizes, are also captured here. This document acts as the project’s “visual bible” and is essential for ensuring external vendors or outsourcing studios can perfectly match the in-house artistic standards.

Sketching

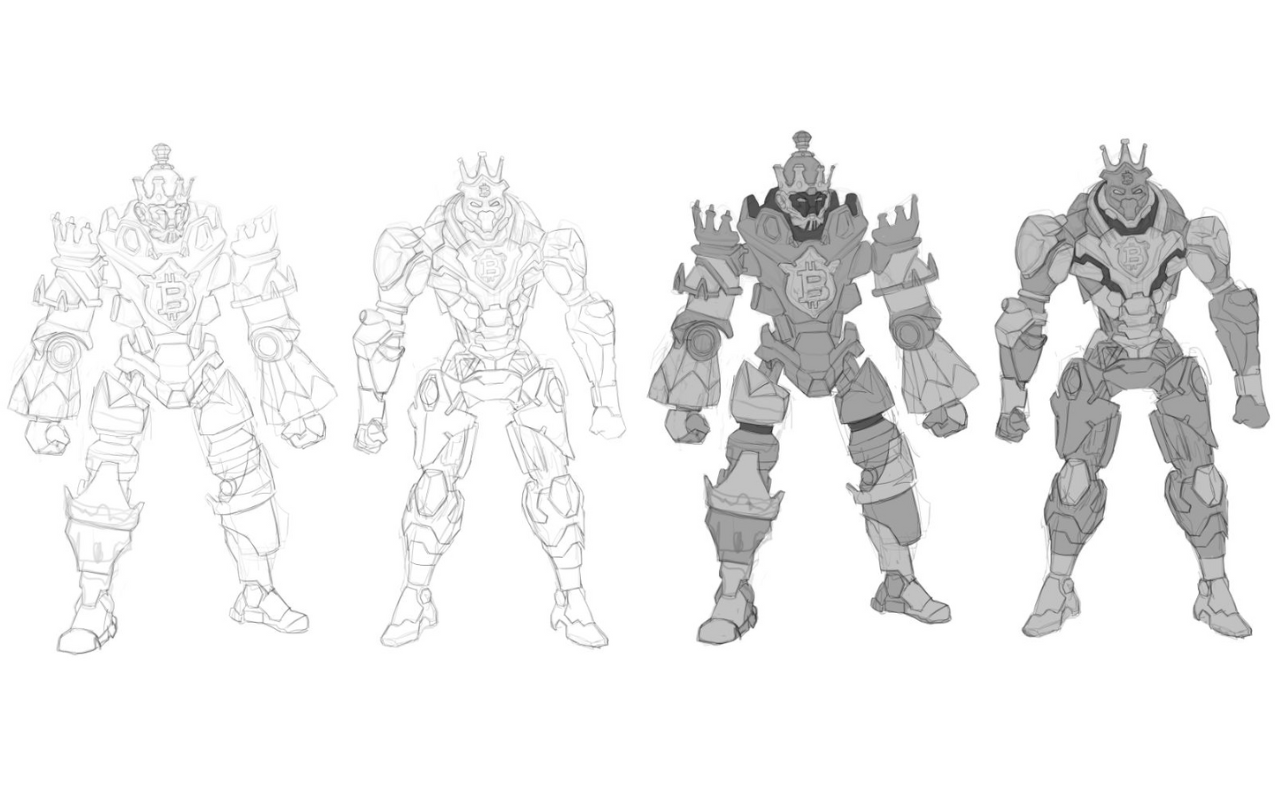

After understanding what the game should be, the first part of the concept art process is when artists start drawing multiple sketches of characters, environments, and props.

Sketches are what artists experiment with ideas and concepts before committing to a final design. Sketches can range from simple line drawings formed by shape language to more detailed drawings.

It’s important to know that sketches can include color, but it is not always necessary. However, adding color to these sketches can help communicate design aspects. Sketches can also be used to explore different visual styles and color palettes.

Color Key

The color key is a visual guide used in the game art pipeline to establish the game’s color palette and mood during the concept art stage. Specific color schemes convey the intended tone and atmosphere, creating a consistent look and feel.

Here, the color palette, a collection of colors used together in a specific design, is ready based on the color theory in games. A typical color palette can include primary, secondary, and tertiary colors.

It’s important to consider how the colors fit different assets, such as characters, environments, and UI elements. It’s also important to consider how the colors look across devices and displays under different lighting conditions and environments.

Painting

The last part of the concept art is applying colors to a surface using various tools and techniques for more detailed textures. During the pre-production of game art, painting is done on a digital tablet using tools like Adobe Photoshop or Procreate.

In addition to details, lighting & shading effects are also created by painting sketches. A skilled game artist can create visually compelling game art at this stage of the pipeline.

Asset Planning

Asset planning translates creative goals into a manageable, pragmatic task list. Producers and lead animators jointly develop an asset creation pipeline that covers characters, enemies, props, environments, UI elements, icons, VFX, and marketing visuals.

Each item on the list is assigned a priority (mandatory vs. optional), a complexity rating, and an estimated completion time or cost.

For 3D assets, you might specify the need for rigging, animation, LODs, or alternate skins; for 2D assets, you might specify whether they are static, modular, or frame-by-frame animated (sprite sheets).

This step typically results in a detailed task backlog managed in tools like Jira or Trello. Once the scope is clear and approved, production artists can begin creating content with minimal unforeseen issues.

Prototypes and Test Assets

Prototypes and test assets help validate whether the chosen art style is effective in actual gameplay and runs correctly on the target hardware.

Instead of building the entire cast of characters immediately, the team creates a small, representative collection of assets, for example, one playable character, one enemy, and a small environment segment, to test within the engine. This vertical slice quickly reveals readability issues, performance bottlenecks, or visual style clashes.

In 3D, you might test how shaders, lighting, and post-processing affect the final look; in 2D, you might test parallax, camera behaviour, and UI layering. Feedback from game designers and programmers is vital at this stage.

What Does the Game Art Production Pipeline Look Like?

The production pipeline is where most tangible work occurs: transforming approved concepts and plans into extensive asset libraries. Let’s explore the core stages within this stage of our pipeline:

Character Production

The character design process starts with highly detailed concept art exploring various poses, outfits, and expressions tailored to gameplay requirements.

For 2D games, artists may paint final sprite sheets or individual modular character parts ready for rigging and animation. In 3D, character modelers translate the concept into a high-resolution sculpt, focusing on correct proportions, silhouette, and efficient animation topology.

Art directors and game designers review these early versions to ensure the character is clearly readable even at small gameplay camera distances. Planning for color variations, skins, and customization options may also occur here.

Environments and Props

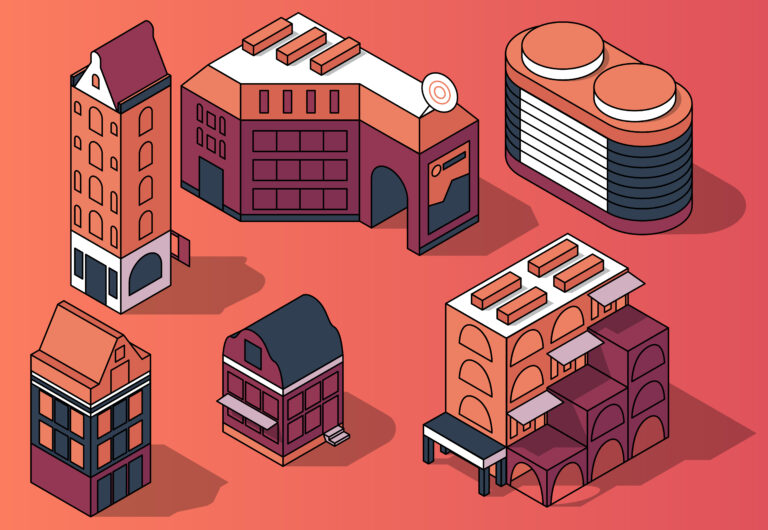

Environment and prop production focuses on constructing the worlds that players will explore and interact with. Environment artists first block out the level geometry to facilitate gameplay flow, then detail it using modular pieces, tiling textures, and visual set dressing.

Props, such as weapons, crates, furniture, or in-world collectibles, are designed to be visually appealing yet instantly recognizable. Prop artists must adhere to the scale, collision, and navigation requirements provided by level designers.

In 3D, using modular kits and trim sheets significantly accelerates production and maintains performance; in 2D, using layered backgrounds and parallax creates depth without high computational cost.

3D Modeling

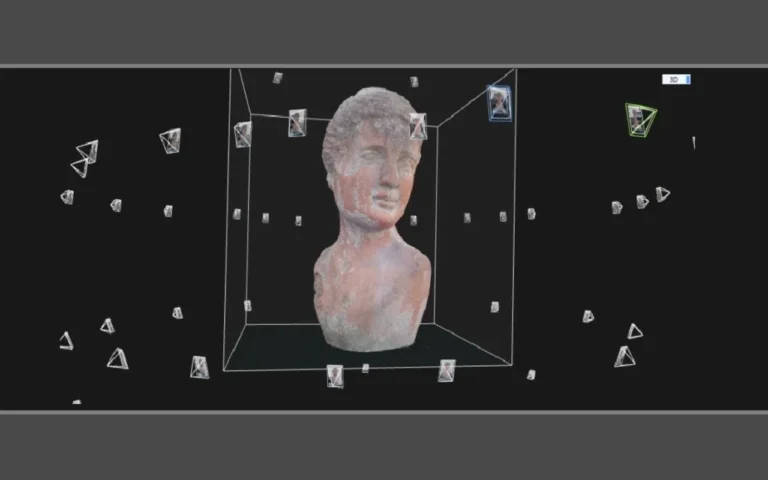

For 3D game art, sculpting, retopology, and texturing constitute a fundamental workflow.

- Artists typically create high-poly models in software such as Maya or Blender to capture fine surface detail, including wrinkles and folds.

- Next, they make a low-poly, game-ready mesh through retopology, ensuring efficient edge flow and animation-friendly topology.

This high-poly to low-poly game art modeling allows artists to cover every base for the final production.

Texturing

Now, it’s time to optimize textures and apply 2D textures onto the surfaces of 3D models in order to add detail, color, and surface characteristics like roughness, glossiness, and bumpiness and enhance their visual appeal.

3D texturing with tools like Substance Painter defines materials, such as metal, fabric, and skin, while strictly adhering to PBR (physically based rendering) standards used in modern engines. The outcome is an asset that appears rich and complex yet still runs efficiently in real time.

Rigging and Animation

Rigging and animation are the stages that bring life and responsiveness to characters and creatures.

Rigging artists construct internal skeletons (bones) and control systems, defining how joints articulate, how the character’s skin deforms (skinning), and how facial expressions function (facial animation). For 2D, this might involve bone-based rigs in tools like Spine or in Unity; for 3D, it requires full-body and face rigs created in software like Maya or Blender.

Animators then create essential movement cycles (idle, walk, run, attack, hit-react, emotes), always prioritizing gameplay timing and responsiveness. They collaborate closely with designers to ensure all movement transitions are smooth and clearly visible.

Integration into Engines

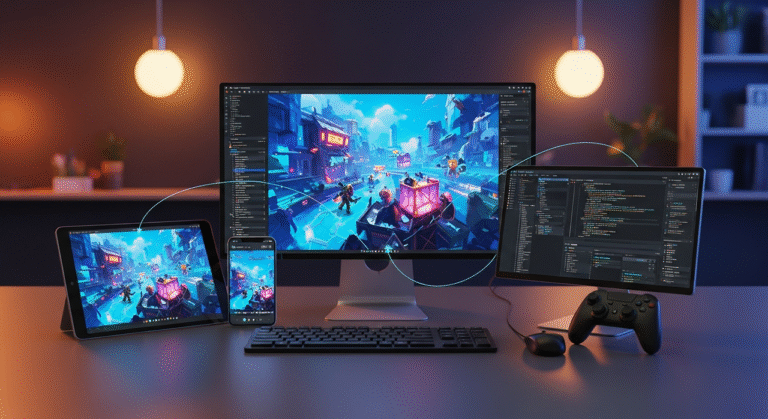

Integration is the crucial link between digital content creation (DCC) tools (such as Blender, Maya, and Photoshop) and game engines (such as Unity or Unreal Engine).

Here, technical artists and integrators import the final models, textures, rigs, and animations, set up the correct materials and shaders, and assign collision and physics properties. They verify that assets use the correct scales, pivots, and strict naming conventions so that programmers can connect them to gameplay systems (like character controllers or inventory).

LODs (Level of Detail meshes), lightmaps, and texture streaming settings are configured for performance. In 2D pipelines, integration includes managing sprite atlases, sorting layers, and camera setups. This stage often reveals minor issues that require a step back (rework), making fast feedback loops essential.

UI, VFX, and Lighting

UI/UX, VFX, and lighting form the final layer of visual information and emotional impact in your game.

UI artists design the HUDs, menus, icons, and in-game prompts to be easily readable across different screen resolutions and input methods.

VFX artists build particle systems for effects like hits, magic, weather, and environmental ambience, always balancing visual flair with the performance budget.

Lighting artists, or technical artists, establish mood and direct the player’s focus by placing lights, tuning shadows, and applying post-processing effects (such as bloom, color grading, or depth of field).

These elements must fundamentally support gameplay, provide clear hit feedback, display readable health, and show visible paths, while also strengthening the game’s unique artistic identity.

What Happens During Post-Production in the Game Art Pipeline?

Post-production is the phase where the art team’s focus shifts from creating new assets to quality control, optimization, and visual consistency. The primary objective is to ensure the game looks cohesive across all levels and runs with a stable frame rate on all target platforms.

Let’s outline the main activities in this post-production phase.

Polish and Refinement

Polish and refinement concentrate on smoothing out every rough edge across the visuals. Artists tweak materials that appear inconsistent, refine subtle character poses, correct animation glitches (pops), and adjust environment clutter for better readability.

Even small changes, such as slightly brightening a key object or simplifying a noisy texture, can dramatically improve player comprehension.

Cross-level visual consistency is thoroughly checked: skyboxes, fog, and color grading should flow coherently throughout the player’s journey. Small details, such as subtle UI micro-animations, improved impact sparks, or minor camera shakes, can significantly raise the perceived overall quality.

This is also the appropriate time to ensure in-game visuals precisely match the project’s marketing imagery. Once polished, assets proceed to deeper optimization.

Optimization

Optimization is the process of guaranteeing that the finalized, beautiful art runs smoothly on the required hardware. Artists and technical teams use optimization techniques to reduce texture sizes (where fidelity allows), merge redundant meshes, fine-tune LOD distances, and bake lighting to minimize real-time rendering and computational costs.

For mobile and VR projects, performance budgets are very strict, necessitating aggressive optimization. Shader complexity is audited, particle systems are simplified, and unnecessary transparency is reduced.

Profiling tools in Unity, Unreal Engine, or platform-specific SDKs are used to pinpoint bottlenecks. The goal is to maintain the target frame rate (e.g., 60 FPS on console or 30 FPS on mid-range mobile) without compromising visual clarity.

QA, Launch, and Live-Ops

In the later stages of production and during live ops (post-launch), art teams collaborate with QA and community teams to resolve visual bugs and create new content.

QA reports will highlight issues such as geometry clipping, animation errors, illegible UI, or broken VFX; artists will prioritize and fix them before release.

After the game launches, live ops often require creating seasonal skins, event environments, and store art that must perfectly align with the original art style guide.

The entire pipeline is reused on a smaller scale for each new batch of assets: concept discovery, production, integration, and optimization. This ongoing cycle is vital for keeping the game visually engaging and meeting player expectations, paving the way for future updates, expansions, or sequels.

2D vs. 3D Game Art Pipelines?

2D and 3D game art pipelines share the same fundamental high-level stages (Pre-production, Production, Post-production) but diverge sharply in terms of tools, the internal structure of assets, and the nature of performance considerations.

In 2D game art, the bulk of the visual work is done through painting, vector art, or sprite animation tools, with the game engine primarily handling layering, parallax, and basic shaders. In 3D game art, there is a heavy reliance on modeling, sculpting, rigging, and complex PBR materials, alongside sophisticated lighting and camera setup within the engine.

2D pipelines typically allow for quicker iteration and are often preferred for smaller teams and tighter budgets, while 3D pipelines are built to deliver high-fidelity, cinematic, and immersive experiences, usually at a higher production cost.

Let’s compare the software, engines, and daily workflow distinctions:

Software and Game Engines

- For 2D pipelines, artists commonly use 2D animation software tools like Photoshop, Clip Studio Paint, Krita, and Procreate, as well as vector software such as Illustrator and Affinity Designer.

Animation may be done in specialized software like Spine or DragonBones, in After Effects, or directly in Unity and Godot using 2D rigs.

- For 3D, the industry-standard game art software (DCCs) include Blender, Maya, 3ds Max, ZBrush for sculpting, and Substance Painter or Substance Designer for texturing and material creation.

- Game engines also have varying strengths: Unity and Godot are highly popular for both 2D and lighter-weight 3D, while Unreal Engine is often the choice for high-end 3D demanding advanced lighting and complex VFX.

Selecting the correct toolchain depends entirely on the target platforms, team size, and the desired visual fidelity.

Daily Workflows

- Daily workflows in 2D pipelines are centered on creating the final renderable frames or layered images: drawing characters, painting backgrounds, organizing sprite sheets, and preparing for cutout animation.

Iteration cycles are often much faster because there is no complex 3D modeling or lighting setup; changes can be painted directly onto the art.

- In 3D pipelines, the workflow is more compartmentalized: modelers, texture artists, riggers, animators, and lighting artists often operate as distinct, specialized roles.

Making a change may require adjustments across multiple sequential stages; for example, tweaking a character’s silhouette might impact topology, UV mapping, and rigging.

However, once the foundational 3D assets are complete, they can be easily reused and re-lit across numerous scenes with excellent efficiency.

Understanding these fundamental differences helps teams choose the workflow that best aligns with their budget and creative visual direction.

When Should You Choose a 2D vs 3D Game Art Pipeline?

The decision between a 2D and 3D pipeline must be based on your game’s design goals, available budget, and the current team skillset.

- 2D pipelines are excellent for highly stylized indie projects, mobile titles, narrative-focused games, and retro-inspired experiences where rapid iteration speed and visual clarity are prioritized over full 3D immersion.

- 3D pipelines are the better choice for AAA games, shooters, RPGs, and highly cinematic experiences that feature full camera control, dynamic lighting, and complex environments.

- Hybrid approaches, such as 2.5D animation utilizing 3D environments with 2D UI, are also common.

Before committing, carefully consider the tools your team is proficient in, the platforms you are targeting, and your long-term plans for content updates and expansions.

Final Words

The 2D and 3D game art pipeline is not merely a checklist; it is an organized, strategic system that keeps development teams synchronized from the very first sketch to post-launch updates.

By mastering the steps of pre-production planning, production workflows, and post-production polish, you can effectively prevent bottlenecks and deliver visually cohesive games that run smoothly on your target platforms.

Whether you ultimately opt for a 2D, 3D, or hybrid approach, the core principles remain constant: a clear art style guide, realistic scope management, disciplined asset integration, and continuous collaboration between art, design, and technical staff.

Use this guide as a starting blueprint, then adapt each stage to fit your team’s size and toolset to build a robust pipeline that can successfully support your next title and beyond.

FAQs

What exactly is an art pipeline in gaming?

It’s a structured workflow. From concept and design to pre- and post-production, where assets pass through specialized roles.

How many artists are needed for a typical game art pipeline?

Team size varies by project. Small teams may have generalists; AAA titles rely on specialized roles like modelers and technical artists.

What skills do 3D game artists need most?

Technical artists, in particular, need skills in tools, shaders, VFX, rigging, and problem-solving to bridge art and programming.

How does using 3D for 2D games speed up production?

3D workflows allow reusing and animating 3D assets across perspectives. It is faster and more flexible than hand‑drawing every frame.

What are the 3D production pipeline stages?

It follows sequential steps: pre-production, modeling, UV mapping, texturing, rigging, animation, lighting, rendering, and compositing.